Eleven and a half hours. That is how long he sleeps without stirring once. I wake at dawn and head out into the damp dark to run with only the glow of the waning moon to show the way. I return, stretch in the dew, walk the dog, pack lunch, shower, and bring the water to boil for oatmeal. He sleeps on and on.

This is what happens the night after the day the kid rides his bike to the school and back all by himself. Not all by himself, actually — training wheels notwithstanding, he is still skittish about hills. When we come to the top of a slope, he slows to a crawl and asks, “Mommy, can you hold on, please?” I touch the handlebars the way I remember learning to hold the barre in ballet. This lightest of grips is poised and at the ready. When he hears a car, he tenses and turns back three or four times to look. He veers in a wide arc away from the curb. I tell him the story about hitting the telephone pole when I was learning to ride a bike even though I was staring right at it. “You tend to go wherever you are looking, so keep looking at the place you want to go, not the thing you are trying to avoid.”

“I am going to run over that black spot,” he says. He peers with great intensity at a tar patch on the street ahead and steers his front tire over it. “Now, I am going to go over that one.” The cars pass on by.

At the playground behind the school, we run and run and run and run. It is dusk and the storm clouds are rolling in. I chase him up the slide and down the ladder, up the fire pole and down the parallel bars. We do not speak. This game demands no negotiation of rules. He bends and peers at me from between poles across the yard, eyes flashing and skin on fire. He breathes hard and braces himself. I charge and he shrieks, mulch flying. He tears off over the jungle gym and under the bridge, ducking, faking left then right. His wild laughter echoes off the school’s brick walls. We run until he notices the sky.

“Those clouds are very low,” he says.

“Yes. They are.”

“We should go home.”

He is back on the bike and I drop my fingers onto the handlebar. He nudges my hand away. “No, Mommy, you don’t need to hold me.” He weaves in and out and around the pillars at the front of the school building, tires churning up the chalk murals of peace signs and rainbows. On the way home, we meet the slope going the other way. He lifts his hands from the bars and gazes at the red, puffy spots on his palm.

“We can put ice on your hands when we get home,” I tell him.

He makes a fist, releases it, then pushes on.

“They make special gloves for biking,” I say. “They have padding and no fingers. We can get you some.”

“I’ve seen them,” he says.

And now he is climbing. Up in the seat, he stands as he pedals up the hill, grinding against gravity. I grin and tell him he’s got it. He climbs all the way to the top hill and then drops into the seat, pauses, and looks at his hands again. The red spots are angry now.

“We’ll use that soft ice pack,” I say.

“Okay.”

He turns right at the stop sign and continues all the way home. He never asks for my help, never complains. He makes it to the driveway and then lets me maneuver the bike into the garage. Inside, we root around in the fridge for the ice pack. He presses his hands to the blue pockets of relief.

When I put him to bed an hour earlier than usual, he does not protest. We read our three books and sing our three songs, cuddle and nuzzle and have butterfly kisses.

It is no surprise he sleeps on and on this October morning. When he wakes and comes padding into my room, he tucks himself under the already made folds of my comforter, grinning with sleepy bliss.

“Can you come cuddle me, Mommy?”

“I can cuddle you for exactly one minute. We have to get ready for school.”

I lay down next to him and put my face against his. He turns and presses his nose into my cheek.

“How about exactly two minutes?” He puts his hand on my arm. The red blister has faded to a pink whisper.

“Okay,” I say. “Exactly two minutes.”

He hums into my neck, closes his eyes, and pulls my arm across his belly.

Tag: children

Happy 100 Days: 93

At bedtime tonight, I learned that almost 6 is not too old for “this little piggy.” When the kiddo pulled off my right shoe and sock, I learned that almost 39 is not too old for it, either.

Happy 100 Days: 94

At the Colonial Farm Park, we walk back into 1771. It is all bonnets and woolen trousers. The family living there hangs tobacco in the barn to dry. The cast-iron belly of a pot hangs low over a fire that heats a potage of turnips, onions, and potatoes to boiling. The children are at work pulling “mile o’minute” from the fence with large wooden rakes. The skinny black cat is stuck in the tree, but one of the women uses a thick branch to help him down. As soon as he is back on the ground, he races off to terrorize the chickens.

Bug and his friend scoot around the corner to get in on the action when the clutch of young people returns from rounding up a loose piglet. A boy tosses darts made of corn cobs through a hoop. The girls spread their skirts and rest in the shade before supper. They show the two children from the future their dolls made of twisted corn husks wrapped in scraps of hand-dyed wool.

The place is inches away from one of the most congested metropolitan areas in the country. Or rather, what will become such a place in another 250 years. My friend’s little boy points out a cumulus cloud. A leaf falls into the collar of his shirt and he giggles. I hear the geese jabber at someone passing over the hill.

Time passes. Maybe a long time, maybe not. My friend and I talk, sitting on stumps outside the warming face of the log house where garlic dries in the rafters. Bug and his buddy are somewhere out of sight. A chicken squawks its disapproval at the relentless kitten. Eventually, Bug comes around to see me.

“Mommy, do you know what we are doing?”

“I have no idea.”

“We’re building a dollhouse.”

We rise and shake of the torpor. Indeed, he and my friend’s daughter have collected fallen sticks and sleeves of bark, gathered stones, overturned logs. They continue to balance these mismatched building block across one another, higher and wider. All around them, the skirts spread, the bonnets loll. No one speaks. Somehow, the house is erected.

My friend and I sit some more. Later, we wake, and 20 years has passed. The sun has moved our rough seats into the shade. We shiver a little and pull sweaters back over our sunburned shoulders. When we leave, we find the children have assembled the corn-husk family in its new quarters. The rooster struts past, swishing his black-ringed tail. The kitten watches from a distance. Everyone is ready for winter.

Happy 100 Days: 97

Reasons for gratitude on the day the teacher emails half a dozen times in 24 hours, calls home once, and sends the kid to talk to the school guidance counselor:

- The teacher emails and calls when the kid is having trouble.

- The teacher responds to email replies and returned calls by providing additional information and suggestions.

- Tee copies me on every correspondence with the school (and I do the same for him) even when the teacher forgets.

- The school has a guidance counselor on staff who has time for kindergartners

- My kid has a whole team of caring adults supporting him.

- Next year, he will have a different teacher.

- At the end of the school day, he can run off all that accumulated talking-to and think-iness at Chicken School.

- Grandma makes a veggie lasagne and pulls it hot out of the oven as soon as we walk in the door.

- At bedtime, Bug stumbles across his first word search in the coloring book he brought to bed. Fascinated, he looks for the correct adjacent letters then draws his brown crayon around the words, “hunt,” “movies,” “safety,” and “tell.” He sounds out each letter, following along with the key at the top of the page.

- After books and songs and cuddles, Bug presses his face into mine, kissing my cheeks sideways. He giggles twice then rolls over and falls fast asleep.

Full Spectrum

Why did I hesitate to put all this glory of the sun on my canvas?

– Paul Gauguin

Every parent compromises. We breathe through our uncertainty, living in the world as it is while occasionally dotting the page with what could be.

We put Bug on the rolls for the county School Aged Child Care Program when he was only four years old. A month into kindergarten, and he is still number 72 on the waiting list. They tell us he might get in by second grade.

Tee and I spent a good portion of last year exploring every day care option in the area. We found homes crammed with untended children staring, gape-mouthed, at Dora on giant TVs in converted basements. We found KinderCare centers with such an avalanche of scathing online reviews that we had to restrain ourselves from taking up arms to liberate the children inside. The nearby private schools only provide after-hours care to the gilded young who already attend.

Word on the street is that the Tai Kwon Do place in a local shopping center is decent enough. It has vans that pick up the kids after school. The teachers give their charges a 30-minute martial arts lesson, a snack, and play time in a small nook at the back. Bug and I visit on several occasions. The kid’s default is to notice the things in front of him, and he has only just begun to long for what is absent. Bug does not even register the adjacent nail salon or the lack of outdoor space. These are my issues, and I buoy my tone up above the churning resistance in my belly. Watching the students practice their kicks and shouts, Bug bounces and begs to join.

Not even a postage stamp yard for a jungle gym? Cramped quarters? A Leviathan flat-screen TV in the back of the room where the after-school kids gather? I force myself calm with little mantras. It’s only temporary, it’s only a few hours a day. He’ll be fine (and even if it’s not, what can I do about it? We can’t afford a nanny or a private school, and I have no choice but to work).

I only allow myself a single blink at the image of what I want for Bug. The saturated hues are bright enough to sear. It seems so foolish to covet the impossible, but I know exactly what it is: Real. Living, breathing, tactile, sensory. A wide-open green place where he can run and climb. Games and balls and unscheduled time with friends to spread out on a floor to paint or build. I want there to be no electronic babysitters. I want adults within reach that understand child development but also back off and let their charges find their way. I want Bug to get bored and wander through that uncertainty until his hands take up some task that speaks to him. I want him to track the seasons by simply being among the trees. I want what so many parents want: My kid tapping into his unlimited self on the living earth, playing hard with his whole brain and body engaged.

What is the use of giving shape to the impossible? We are poor(ish), nothing better exists, and I have to work. So I do not give that Real more than one swipe across the canvas before setting down my brush. This is as good as it gets. My wildly outdoorsy kid will only get to play in the fresh air on weekends. He’ll go to a good kindergarten, and be blessed by the fact that his dad and mom both love camping.

Tee and I sign the contract and pay up. Bug would spend 15 hours in a strip mall. Breathe, lady.

When mid-August arrives, we put Bug in the Tai Kwon Do day camp for a few days to acclimate him. I pick him up at the end of Day 1, and he tells me about their trip to the park and their short martial arts lesson.

“What else did you do?”

“Watched a movie in the morning. Then we watched another movie when we got back!”

Day 2. The field trip is to – yes, you guessed it – the movies.

“What else did you do?”

“In the morning, we watched a movie. After Tai Kwon Do, we watched another movie!”

Three movies in one day? Bug is very, very happy at this turn of events.

Day 3. The field trip is to the pool. This time, when I drop Bug off, I walk with him all the way through to the child care nook in the back. The chairs are lined up in rows. The TV is blaring Disney’s Peter Pan. Not a crayon, block, or board game is anywhere in sight. I have never really looked around before, but now I see that all the cabinets are stuffed full of martial arts equipment. The floor has no train set, no bin of legos, no easel or pegboard. The bookshelves house trophies. The tables are bare.

This is not a child care facility. It is a storage closet.

It is 8:00 in the morning, and I am paying this place for 9 hours of DVDs. I could take him to work with me and provide that kind of childcare myself for free.

I leave in a panic. In two weeks, school will start. This is what awaits my son? During the commute, I turn my universe upside-down trying to shake out another choice. Maybe I could quit my job. Maybe Tee and I could get back together and I could work so he could stay home, which is what he wanted anyway. Maybe I could beg my mom to retire. Something? Anything?

There is only so much compromising any of us can do. At some point, we hit the core of what we believe about the world, and we either have to change what we believe or we have to change the world. I can put my kid in a strip mall. I can contort my schedule into a pretzel to accommodate easy transitions before school, as I described in this post about the enrollment choice. I can even allow the occasional hour of Nick, Jr. if it takes place at the end of a dynamic day full of real life. I do believe in letting go of some rigid plans for my child.

But I also believe in the open sky and in the beautiful play of the body and mind when they are free to roam. I believe far too deeply in calling out the pulse of our humanness, of our mammalness, at every opportunity. We dull too many edges with our entertainments and ill-conceived inventions. We grow numb far too early, and we rebel far too rarely. When my son was born, I made a quiet promise to him and to the world for which he will someday be responsible: My child will have poetry and he will have the earth under his feet, and he will learn to be a steward of this precious place. Even if it means I throw out the safe-enough income, the health benefits, and the someday-home-of-our-own, my child will have the real. I will work part time and live in a rented basement before I let him spend his 42 weeks a year in a place that thinks it’s okay to stultify our beautiful young ones with three #&%*$ movies a day.

I arrive at work and start trolling. Internet. Phone. Someone, somewhere. Every place within the zip code of Bug’s school, I check again. Same names of the same desperate ladies in their cramped townhouses with the TVs doing the babysitting. Same big-box profit-hungry franchises. Same elite institutions with no transportation provided to and from the public schools. I expand my search to the next zip code. I have already cried twice, and it is only 9:00am.

Then. I stumble upon this place out on the very edge of the district boundary line. The website describes hands-on learning, farm animals, and free play. It is country day school, drawing on Dewey’s experiential roots and the progressive tradition.

I call. “Do you have openings for after-school care?”

“Before and after-school, yes.”

“You are in our elementary school district? Really?”

“Yes. The bus picks up here in the morning and drops off here in the afternoon.”

“Can I kiss you over the phone?”

Giovanni, my knight in shining armor, takes a hiatus from work, picks me up and whisks me over the twisting country road past million-dollar homes and horse barns. We pull up to the address and step out into the sun.

Into the Garden of Eden.

Five acres of land. A sledding hill. Two playgrounds with hand-hewn wooden play equipment. Chickens, a goat, a pony. Jumbled flagstones wind through an overgrown garden and pumpkins spill from vines behind the fence. Peeling layers of children’s art plaster the walls of an old, rambling house whose rooms are cluttered with books, board games, blocks, balls.

Other than a single computer in the office for the Assistant Director to send emails to parents, electronic screens are verboten. The bus ferries kids between this paradise and Bug’s school every morning and afternoon. Even with the addition of the before-school care we need, this utopia is only marginally pricier than the Tai Kwon Do place.

Most importantly, there is room for my son. Plenty of room. Acres and acres of open sky. He can run with his arms stretched out and swallow the whole day.

Now, when I pick Bug up at what he calls “the chicken school” at 6:15pm, he is pink-cheeked, grubby, and usually perched at the top of a jungle gym lording over the playground. He does not want to leave. I sit at the picnic table and watch him dash up and down, past the rabbit in the hutch, over the relentless weeds, dust flying.

For a time, I did not believe in anything but the limits of this new life. I did not allow myself to see in color because the dulling gray of resentment and grief had so blanketed the beginnings. Leaving behind a marriage, a life in the mountains, and dreams of a happily-ever-after can bring on temporary blindness. It hurts so much, that distance between what is and what could be. It hurt enough that I built a prison in my mind and stopped letting in the light. It is safer there, no?

Stay there long enough, and the temporary condition becomes permanent.

I have spent far too many years – years well before Tee – only letting my trust go so far. This here is enough, I say. This here is as good as it gets. I will learn to live with it. This time around, desperation forced my hand. I hit the core of what I believe about the world and teetered on edge of trading my faith for a release from the duty to serve that calling. A small existence may seem a safer bet than facing the possibility of change, but it’s an awfully expensive deal. A compromise of that magnitude is pure capitulation. Thank goodness the pulse of life is stronger than my cowardice.

This gift of a perfect way-station for my son arrived at the moment I refused to settle any longer for just good enough. I want to hold onto this small truth: it is an act of courage to believe there is more to this journey than surviving on scraps. It is never too late to voice desire for what can be, to dip the brush into the richest colors, and to use the whole spectrum to craft a life.

No more picturing toil and limits. No more hard, dark images of poverty. I shake off the hair shirt and surrender the title of martyr. Artist is much more to my liking. I pick up the brush. I paint the world abundant, and so my son and I are rich beyond measure.

Inheritance

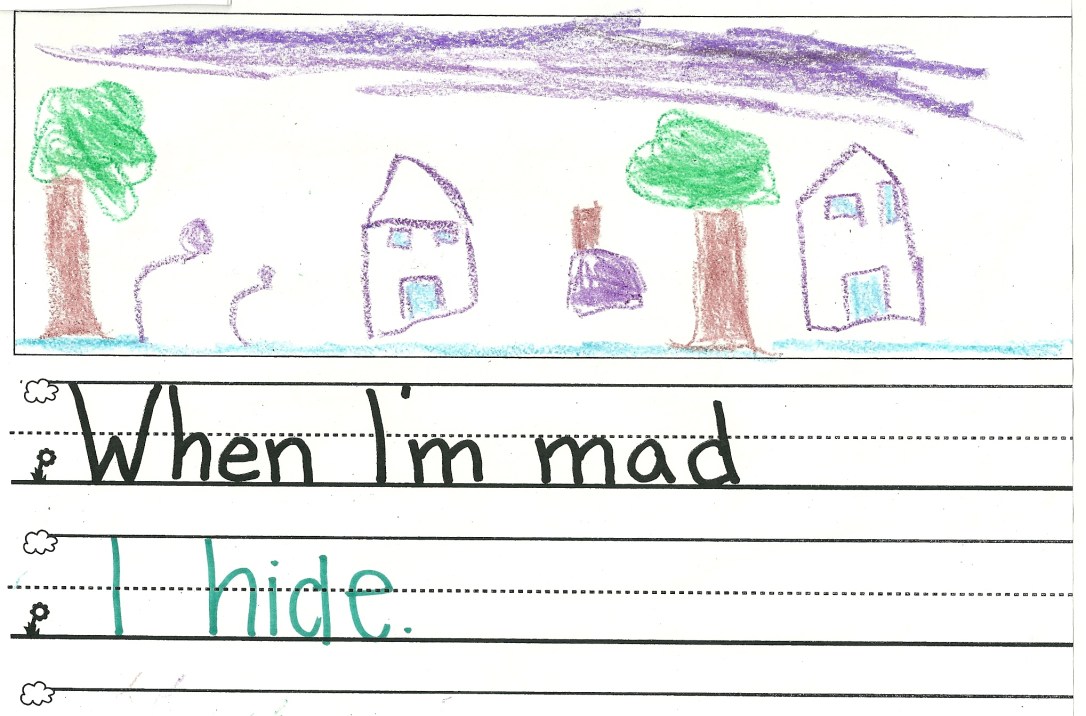

Me: “Tell me about this picture.”

Bug: “That’s my two houses. Your house and daddy’s house.”

Me: “Are you hiding behind one of the trees?”

Bug: “No. I’m hiding in that brown and purple thing in the middle.”

Me: “What is it?”

Bug: “A little teeny tiny house. No one can come in but me, and I can do anything I want in there.”

Me: “Like what?”

Bug: “I can say ‘shut up’ all I want.”

Me: “What else do you do?”

Bug: “You know what else.”

Me: “Um. . . let’s see. You watch TV?”

Bug: “Yep. That’s what I do. I watch all I want. I watch TV all day long.”

Shot in the Dark

“Are they going to give me a shot?”

“I don’t think so, baby. It’s just strep throat. They’ll give you medicine. The kind you drink.”

“But are you sure? Do they ever give shots for strep throat?”

“Not that I know of. But I can’t say for 100% sure. You know what you do get at the doctor’s? You get stickers. And they put the cuff on your arm, and we find out how tall you are and everything.”

“But are they going to give me a shot?”

It would be so easy just to tell him what what he wants to hear. That “no” would ease his mind and get him off my back. Nevertheless, I refuse to submit. I will answer his question 147 times as truthfully as I can even though a single lie would quiet his fear.

The mind has a way of spinning out of control once it has fixed on a worst-case scenario. Untangling the knot of obsessive thoughts becomes even more difficult if a past hurt has laid down an association between experiences. Rock climbing = broken limb. Making art = ridicule. Professional risk = debt. Love = heartbreak.

Doctor = pain.

Mystery ailments haunted Bug from his first birthday until his fourth. On top of the bombardment of normal childhood immunizations, the poor kid had blood drained from his arm several times a year. Is it any wonder he starts fretting about injections before we even make it through the door? He clings to my leg and urges me to ask about shots. The nurse smiles and gives wheedling reassurance. “Oh, no, big guy, no shots today.” I feel Bug relax his grip and begin to look up. We stride down the hall to the exam room.

Then the doctor comes in and checks his chart. “Oh, we need to take a little blood,” she tells him. Bug contracts into a fist. His eyes flash in my direction. Sighing, I shake my head. “I’m so sorry, buddy.”

This contrition. For what? For his having to feel pain? No, the needle is not the real hurt. My apology is for the falsehoods of grownups. It is for those of us who choose compliance over presence of mind. Maybe the adults of the world are just too rushed to speak the uncertainties. It’s easier to zip on past a hard conversation, scoot the kiddo to the next room, and keep everything humming along. We have a schedule to keep, after all.

Every time this occurs, I see one more brick in Bug’s foundation of trust crumble. While I understand the argument that life is not fair and kids need to learn that the world does not always deliver on its commitments, I do not agree with the premise. What is this need we have to make promises we know we cannot keep? Living with unknowns is a much more powerful skill than living certain that people will lie.

I want my son to learn how to orient his attention in the face of his demons.

No one ever tells us to stop running away from fear…the advice we usually get is to sweeten it up, smooth it over, take a pill, or distract ourselves, but by all means make it go away.

― Pema Chödrön, When Things Fall Apart: Heartfelt Advice for Hard Times

The misery of children makes most adults uncomfortable. We want to allay it or make it stop. We want to divert it. We want kids to Be Happy! We want these things for all kinds of complicated reasons, but one of those reasons is that we know the dark power of the mind to spill us down the rabbit hole. Most of us have visited its depths before. And we want children to stay up here in the light.

Wanting it is not anywhere close to teaching it, though.

Positive thinking is not as easy as it seems like it should be. Reducing mindfulness to sugar-coated optimism, which is another form of putting on blinders, ignores the effort involved in re-training the perception to take in a wider selection of what is real. Broadening one’s attention requires practicing with the rigor of a marathon runner. It takes serious muscle to sit still in the face of uncertainty and pain, and building that fortitude requires going through the exercises no matter how the winds howl.

“A further sign of health is that we don’t become undone by fear and trembling, but we take it as a message that it’s time to stop struggling and look directly at what’s threatening us. ”

― Pema Chödrön, The Places that Scare You

“Let’s breathe together, honey,” I tell Bug. I grow very calm and take him in my lap. We sit in the exam room together cuddling close as the doctor checks his vitals. Bug knows that a needle with his name on it is waiting in the lab. His gaze is narrow and his shoulders are hunched. The grinding of the gears inside his panicking brain is almost audible. He is doing what we all do: seeking a way out or around this thing that terrifies him while being unable to resist its pull.

As we listen to the machine beep, I talk in a quiet voice into his scalp. “The doctor is listening to your strong heart,” I tell him. “It is pumping blood all through your body, giving oxygen to your arms and legs, your stomach, your brain.” I touch him here, and here, and here.

The doctor places the stethoscope on Bug’s chest and he pulls in great swallows of air. This is his reserve. He is filling his well. I whisper and keep my hands gentle on his legs. “Everything is working just right to keep you growing and swimming and singing and playing.” Bug does not respond but I can feel his back seeking the comfort of my belly. We will go together to face the blood draw, and he will cry. I will remind him that the hurt is fleeting, and that he is well, and that everything is working exactly as it should. Even the pain. We will talk about this later in the car, about the wonder of nerves and how they send messages to the brain, and how the sting is one way the power living inside his body makes itself known.

Instead of hurling past the uncertainties to find solid ground, I want my son to learn to slow his gait and feel where he is. It is good to sense ourselves suspended above that crevasse. Even children need to learn to stay inside the questions. What holds us? Perhaps just trust. What becomes of us? Perhaps nothing at all.

I only hope that by pausing with my boy here in this place of no answers, I am helping him lay down another pathway in his busy neural network. This one is about orienting to what is right here. Needles, yes, but also breath. Skin and blood, health and a comforting embrace. Pain and fear.

Also love.

Stuck Landing

We will need to limber up for the advanced scheduling contortions set to begin on September 4th. Kindergarten means our little family-ish arrangement has to bid goodbye to the preschool on the campus of Tee’s university. Aligned calendars and an easy childcare commute have been blessings in a rather tumultuous chapter, and now we brace ourselves for a school-year timeline designed for long extinct agrarian families. Bring on the yellow buses, packed lunches, and after-school children’s warehouses.

Into the Deep

“Mommy, I’m swimming!”

“Yes, baby, I see.” I am distracted by my phone as I stand on the pool deck and bicker with Tee about things that only might happen. I have my suit on but I have not yet ventured out. Bug is already drenched, goggles magnifying his eyes to frightening dimensions.

“Are you talking to daddy?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Tell him, okay? Tell him I am swimming!”

I tell Tee that Bug says he is swimming. Satisfied, Bug turns and bounds back into the shallows, but not before shouting, “Come on Mommy! The water feels really good!”

Since he could first form the words, Bug has been convinced he is a swimmer. “I can swim, Mommy. I can!” His confidence can be a little frightening when he is dancing around on the concrete by the deep end. It is something of a comfort to watch him shift into low gear and take things one inch at a time when he makes his way in. He checks the depth. He plays on the steps. He asks for help.

I can’t count the number of YMCA pools in which my boy has splashed, nor can I remember the names of half the lakes. He has lived in water since birth. Since before, actually. He and I swam through my third trimester in a camp pool under the cloudless San Gabriel sky. I first took baby Bug into the water in the Colorado Springs Y when he was four months old. A blink later, he was in lessons. From making bubbles to holding the edge to draping himself over a noodle, he has crept his way ever closer to total immersion. At a few months shy of his sixth birthday, he is still hanging back.

I stash the phone in a cubby and follow my son out to the 4-foot part of the pool. There, he can just barely touch the bottom if he bounces on his toes. His head goes under, up, under. He no longer sputters, scowling into the air when his head slips beneath the surface. He simply dips in and leaps back out, cheeks bright, already on his way across the expanse of blue. Over near the wall is an underwater bench where he can stand firm. He makes his way there, bobbing along.

“Here I come!” He stands, crouches, and then flings himself across the surface towards me. With his legs out behind him, he kicks and simultaneously paddles his arms in a great churning frenzy. His head is under. In 5, 6, 10 strokes, he roars toward me until he stops and lets his feet fall to the bottom. His head pops up and he looks up at me through those googly lenses, water streaming down his face. His grin is as big as the ocean.

I am stunned into a rare moment of silence. Then I catch my breath and begin clapping like a seal on crack.

“You’re swimming, buddy! You’re really swimming!” I reach for him and he hops over to me.

“I told you!” His voice is wide-awake happy, and he climbs up into my arms for all of a tenth of a second before squirming out.

“Again!” He says. He hops over to the edge and grabs on. He shoos me back. “Further,” he calls. I take a step backward. “No, further.” A few steps more and he stops me. “That’s far enough.” His fingers clutch the lip of the pool. He is almost vibrating out of his skin with contained momentum. “Okay!”

He lets go, turns, and pushes off the edge. My boy swims across the water to me.

How does he know it is time? What changed this week, this night? For all of his life, this child needed solid ground. He needed a place to be planted. Then, in one moment, he trusted. He sensed, or maybe somehow knew, that his body would hold him up and that he could carry himself through water that might have been 200 feet deep.

The idea of being “ready” has been rolling around in the noggin for the past few months. When is a person prepared for whatever comes next, and how does the moment make itself known? When does it become clear that it is time to let go or to embrace? To work harder or to step back? To trust? To push off from the edge?

Beginnings leave permanent impressions on the internal chronology. Just try forgetting the moment you heard the words “divorce” or “malignant” or “we’re sorry, but we have to let you go.” Despite the branded scar of the start, transitions rarely have clear endings. The head-down, eyes-front posture into which a person enters in order to move through the sharp-toothed rapids of the in-between can become the normal stance even when the danger passes. After a period of emotional turmoil, the mind braces for the next blow. The simple act of looking up is almost too much to bear. I suppose a person can live this way for years. For the rest of time.

My own personal holding pattern is, for good or ill, unsustainable. The long-term prospect of raising a child on an inadequate income while living with my folks is enough to force me to change course. Because of this, I have started to hazard glances up and out. Oh, how big and improbable all the options seem! Even just fiddling around with the idea about a writing project, a career move, a relationship, or a class can make me feel out of my depth. I grip the wall. I want everything to stay the same, even though I don’t really and it can’t anyway.

I think of Bug there, just all of a sudden letting go. It seems “all of a sudden,” but of course, it is not. Bug is not landing in open water for the first time at 5 ½. His intuitive knowledge comes from immersion (pardon the pun) in a setting that has become almost as familiar as the earth itself. All those visits to backyard pools and lakes and YMCAs provided the vocabulary. Constant exposure allowed him to make sense of the grammar. Then, one day, a phrase rolls off the tongue. Without thinking, he bypassed the water-wings of translation. One day, he is simply speaking a language.

Practice, then, is key. This I try to do for myself by writing daily, avoiding avoidance at work, and faking glee as I take on bike commuting or designing a workshop. Reaching even in the presence of fear seems to be a good way to develop new habits. New postures, even.

Practice alone, however, only carries things so far. A person can rehearse for a hundred years and never make it to the recital. It is also necessary to understand something about one’s capacity to cross the divide.

Bug may be an astute dabbler, but he has a handier trick up his sleeve and he doesn’t even know it. It is this: my boy never believed himself to be a non-swimmer. The language of limitation was unknown to him. He did not need to unlearn anything in order to make room for a new self-concept. He simply needed to embody a truth that he had already accepted, and let his skills catch up with his confidence: “I can swim, Mommy. I can!”

So, once again, the familiar and achingly simple lesson washes up onto shore. First, picture the dream. Then dip the toes into its rippled surface. Immersion, one inch at a time, and keep the senses alert to the currents. Eyes up. All is possible, and more.

Where do I want to be? What do I look like when I inhabit the skin of my most potent self? Do I let myself believe in the truth of my limitlessness?

Hold the edge, sure, and practice the strokes. As you grapple with gravity, do not let your inner gaze linger on anything but that image of you, surging into the open sea. You never know where or when it will occur. Then, suddenly it does. The shift. The moment of knowing you are ready to take the plunge. Let go, turn, and push off the edge.

From the Mouths of Babes

At the end of preschool’s garden themed week, a picture of flowers with hand-print petals came home along with a plastic bottle terrarium containing threads of newborn sunflowers and beets sprouting from damp soil. This was also stuffed in the bottom of Bug’s backpack. An afterthought? Maybe an infant thought. Maybe a thin strand of desire nosing through the surface of things just long enough to catch the light.