My boy is sad today. He can’t, or won’t, tell me why. He lets me put my arm around him as we walk to the car. “What should we do tonight?” I ask. It is the middle of the week. He has given up (mostly) on asking to play games on his tablet.

“I don’t know.” He climbs into the back seat. We lurch along route 123, Taylor Swift matching the pulse of brake lights.

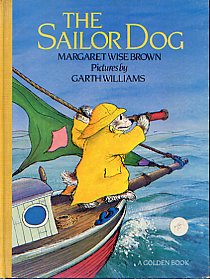

At home, he kicks off his shoes and heads to the couch. He bunches the blue blanket up around his legs. “Do we have any books in this house?” he asks.

This house? Framed in spines, insulated in ink? He must be blind to the floor under his feet. I carry a stack from his room. He opens Toot and Puddle and pulls the blanket up over his lap.

It’s cold enough for a fire. The wood I bought is piled halfway up the wall. The family who split and sold it called it seasoned. The pop and spit of our first fire suggested otherwise. It doesn’t matter. I build a tipi of logs, tucking into its folds a handful of sticks collected from walks around the neighborhood. We have no forest here. Shrubs and maples dot the path that crosses the park and weaves around the AT&T complex. After gusty nights, I gather kindling, cracking limbs across my knee. Cars hum past on their way to the interstate, mothers push their babies in swings. Like a latter-day homesteader, I wobble through the warren of townhouses and condos, bending low to add another purple-gray branch to the bundle spilling from my arms.

Damper open, wind hums down through the cold throat of the flue. I roll up leaves of the Sunday sports section to help things along. With a crackle and low groan, the pulped, broken trees burn back to life.

I should start dinner. From the couch across the room, clunk, flip, flip, clunk. Bug skims then discards. After a few moments, silence. With the iron poker, I press a knot of classifieds under the grate. The ends of the branches flame to orange, blacken, curl. Log grains catch.

These things we call fallen, they burn.

I feel him next to me. I pad to my room and drag the turquoise fleece cushion from my bed out to the warm floor. Our Christmas tree, fatter than it has any right to be, twinkles purple, green, blue. I click on the tea kettle. Bug has carried over three books. A graphic novel, a Magic School Bus, a re-take on The Nutcracker. He leans against me.

“Hey buddy. Do you want me to read to you?”

“No, I just want to be close.” He sprawls on the cushion, face on my leg. Popping embers. Rising steam. The water is ready but I’m not. In the orange glow, he turns pages.

The heat works its way down to my sternum. Into my bones. This is what it is to unfurl. It is drinking light. We’re a year and a half in, and still, I marvel. We actually made it here, to this spot on this golden bamboo floor in our own home. Half a decade ago, I couldn’t even fathom what we’ve now mastered. My boy learned to ride a bike this year. He can already stand in the saddle, legs pumping to climb the big hill to Bob Evans. He can sink a shot from the foul line. Draw zombie comics. Approximate the square root of 11. Make breakfast burritos on the stove from scratch.

My boy can read. Beyond making sense from syntax, he can really read. On a Thursday evening in January – now or 2035 – he opens a book and finds tucked into its pages a nest made just for him.

Bug sighs and turns to look up at me. “Can we have extra reading tonight?”

“Of course, baby.” Stories fill our corners, swathe our sofa, clutter our coffee table, carpet our floor. Stories, ours, all of them. The ones we read.

The one we write.

These things we call buried, they thrive.