When you heat the sugar and butter, you have to keep the temperature low. Never stop stirring. This means either working backwards or having a helper handy. Ideally both. When it is time for the vanilla, you will not be digging in the cabinet for it, unless you like your caramel smoked. The candy thermometer will become goopy and steamed, the phone will ring, and you will remember you forgot to butter the pan. Do not turn around. Whoever is on the other end cannot chop the pecans for you, and that person has already bought Christmas cupcakes for her kid’s class.

You wanted to use your hands. This is what you get: a burnt fingertip from believing the thick taupe suede to be a solid thing, just because your tongue was fooled into longing for something it would have had anyway, given one teaspoon of restraint.

Nothing you buy from the store will be half as good as even your most mediocre effort. This is what you know to be true, even if the sequined and tiara-studded confections behind the glass case whisper their siren song. Keep stirring.

Do not check the recipe again or grab ice for your blister. You know the steps by heart. You know the hard-ball stage cannot be rushed and will never be passed – never, because the kitchen clock always moves as if treacle has gummed the gears. Turn down the flame. You should not be able to hear it roar. The only sound that will come is the low moan of the air making its sluggish escape from the candy as it roils. Keep the spoon moving.

The recipe card is written in your grandmother’s script. Shaky, even then. What a thing, her hand: here and also not. Perhaps alive somewhere, in its way, because of microbes and the relentless pull of decay and rebirth everywhere, even in that crimson box they lowered into an Oklahoma hilltop a decade ago. A decade!

This, too: she, alive and also not. The jagged flourish of her script is frozen in motion all the way onto the next line. The 3×5 card is yellowing and blotched with boiled fat, caramelized Karo, and something hard. Another dish, maybe? This recipe, caught in the holiday crossfire. Cornbread stuffing, perhaps, or the clove and orange peel glistening on the crusted pink hide of the sacrificial ham.

She did not stop until her heart did. But which was she? The heart? Or the girl whose powdered cheeks betrayed a heady blush as the boy whirled her across the dance floor? She kept her hands so pliable, the old lady skin as delicate as honeysuckle petals and just as fragrant. How she managed this is one of life’s great mysteries. She stood over boiling sugars and popping Crisco. She took up the catfish who’d been, just that morning, blissfully sucking mud at the bottom of Murray lake, and dragged the poor fellow through bread crumbs and egg before releasing him to his oily fate. She donned the apron and held at least one corner of that restaurant’s kitchen on the hollow bones of her narrow scapulae.

Even so, nothing caved in. No part of her contracted into hardness. The blisters didn’t callous and the wounds of her unplanned servitude never thickened into scars.

When she was in her final year and no longer venturing near the stove, she asked me to rub her hands. Beneath that most delicate tissue purpled like Monet’s garden were thick, arthritic roots delving down to the springs below, blocking the way. She ached all over. “Oh, sugar, it hurts something awful.” She had spent a lifetime trying to restrain the tears ducking just behind her voice. She’d spent that same lifetime failing.

I took her hand and pressed into the tender meat between the thumb and forefinger, holding back my full strength because by then, she was made of air and moonless night. Her marrow had long since leached out into the prairie grass for the copper cattle and oil rigs to pull back up when the time is right.

Those last years, she was draining away but age had not taken her best self, only the extra, the unneeded weight, the constraining thoughts. The only things left were softness and pain. Also those relentless tears. Also the bottomless hunger for touch.

They say that if luck favors us (or scorns us, as the case may be) with a long enough life, each of us returns to infancy.

With my fingers, I drained what I could of the useless strength in her hands. What was the use of muscle and its dedicated ache? What did she need with holding? I had taken up her place at the stove, the ink, as the bearer of a name on my own more robust shoulder blades. My only job was to help guide her back gently to the womb of a woman waiting on a hill in the morning sun. That matriarch had herself returned to forgiving clay. At last, the serrated edges were worn from her mother’s tongue.

In the trunk I hauled from the foot of my grandmother’s bed into my own home 1500 miles away, I find the gloves she had worn in an earlier life. The embroidered delicacies are white kid and cotton, hand stitched and studded with graying rhinestones. Also from that steamer trunk rises a gust of the same aging honeysuckle that clung to her and forever softened her.

This was her secret? Something so simple? The gloves do not fit over my swollen knuckles. Thick digits already leathered in the first third of my time on this planet strain at the seams (though I do try to force myself into that silken sheath. Who wouldn’t?) I put them away for a keepsake since they will never grow to envelop me nor will I, God willing, ever shrink sufficiently to squeeze in.

I close the trunk and wonder if her determination to stay soft was the toughest part of her. Her man may have cornered her in that crucible in the back of the restaurant. Necessity may have demanded she plunge her hands into whole chickens and dice bushels of yellow onions for the soup. She may not have had any real choice but to stir and stir those cauldrons of beef and butter beans for paying customers. Kids and mortgages greeted the young, bewildered families at the end of the war. And maybe it was impossible to buck a man built of the same stuff of stud bulls and dust bowl hickories.

Maybe all of this is true.

Also, she chose.

Do not be fooled: selecting from among just one option is its own act of defiance. Submission is never truly complete as long as the one doing it decides to submit. Somewhere down below even the most bending grass is one deep root that cannot be split, not even with the sharpest spade.

And so she stayed. With him, she stayed:

Soft, the most tender, and forever threatening to tremble into a watery mess. She stayed:

Alive ten years beyond him, then a few more. She was the one whose hands rested in the warm grip of her grown sons and granddaughters during her final months. It was her timeline that claimed a stretch in which the tears could come without reprimand. She let them come and found, to no one’s surprise but her own, that on the other side of pain, when someone finally rubs it free, all that’s left is a heap of stupid giggles, memories of first kisses and big-eared boys, and a craving for the caramels made in the cluttered kitchens of the women who taught us to keep stirring.

Tag: love

Trick of Light

The Boy who Refuses to Smile sits down on the low wall next to the girl in purple tights. He leans into her and she into him. She wears sequined high-top sneakers and sparkles like a star. The third child climbing onto the bricks is a nameless shadow, near but in a different frame, on another block, in someone else’s story. The Boy pastes on the requisite grin and stays still for one, two, three cameras. He angles towards her glitter. Their knees touch. She tilts her head and smiles like a diva.

“Oh, so that’s Bug,” the girl’s uncle says. He steps closer to me and introduces himself. “We hear your boy’s name around our house all the time.”

Tee and I grimace at the same moment. I brace for the kind-yet-careful description of our son’s latest wave of schoolyard tyranny. The aunt laughs. “Nothing like that. I think there might be a crush.”

Bug slides off the wall and darts ahead before turning and coming back for her. “Star, come with me!” She runs after him. They clomp up the steps, peering into an offered cauldron and digging for some just-right wrapper. When they hustle back down through the cluster of Iron Men (three of them) and princesses (countless), Star’s pumpkin swings from Bug’s forearm. Star pauses to beam up at the assembled adults.

“He’s carrying my candy for me because it’s so heavy.”

Bug races forward and doubles back yet again, calling into the little girl’s face as if from across a moor. “Star, this way!” He points to foam webs slung from the railing and plastic swords dripping like stalactites from low branches. “That house is for sure open.”

“Okay!” she cries, sliding the pumpkin back off his arm. He waits while she does this. They break into a run towards the orange lights flickering against dark faces, a glass door opening to greet them.

Join

My husband pulled the bobby pins from my hair one by one and placed them on a table in the dark. He ran the brush through with more care than I had taken even as a little girl, even with my china dolls.

Proximity becomes porosity. We were limestone in rain. The monuments to ourselves etched with begets and allegiances weathered to shadow before we could rub the shape into permanence. It was tomorrow and then the next century.

It will be ten years ago we met. Then two griefs and three oceans ago.

Now I lay in wonder in arms I don’t deserve and he traces beauty down into my skin. Into follicle, he hushes a whisper of first light. Even my pores are seen now. Seen and seeing, as if freed from blindfold and handed a mirror in the same staggering moment. “Oh, so this is what I have become.”

He asks questions no one ever should of a girl whose voice was just hatched. Then he marvels at the tears when all we’ve talked of is sweet things. He can’t know how ill prepared I am for this act of dedication.

How lazy these hands.

How hesitant this contained force.

Of course, he does know, and he fixes himself to the spot and draws closer. We quiet ourselves for a moment words cannot reach and listen to the song on shuffle.

“I am going to come up with an adjective,” he says. Then he tucks it away and we let Regina Spektor fill the room and also us with what we can’t yet tap in ourselves. Halfway between hard and soft, her lyric is a silver glint in the dark. An unsheathing ssss of steel pulling free. She holds the blade against our wrists and turns it this way, that, to feel where it curves and where the slanted script at the hilt edge sips in just enough of the offered light to wet channels between lines

and flings away the rest to flash against a corner of the room

the corner we only just noticed

had been wearing a cloak of shadow

over an old table, a handful of hairpins

a corner we never realized reached so far back

beyond walls

that were almost never there

Beautiful

It’s that

lifted cheek. Those improbable toes. The scent of raspberry in the fold of a yellow rose. That flourish in bottle blue mosaic, this single climbing vine. That black damp and wingbuzz at the mouth of shuttered copper mine.

This fountain. A canyon. That monarch. Those mountains.

It’s that

way his back bends when he feints low and away from his aim’s first trace. This just-right note down in the smoke and bass. The kiss under apple blossoms, and come to that, the apple. It’s this skin. The juice.

That taste.

You are, we whisper. It is so, you gasp. Make me feel, I plead.

It’s that

jump shot. Midnight walk. That sword of beam and concrete, this tower of glass.

This hot scalp of infant hunger burrowing into breast.

The swell, the salt, the foaming crest.

It’s that

Do you? That have you? That what if?

This yes.

A first spoonful. A last ember. The clasp on the chain at the back of the neck. That creak of opening, this bed of silk. The light biting at corners. A sweet sucking clench at the intake

of breath before

That letting go.

Your masterpiece in oil and the way water cuts channels through

This everything.

It’s that

key in your hand.

Those notes in script

you can’t read yet.

The drawstring, the marble, the button, the pocket.

The jar with no label.

This canvas still wet.

It is so, you say.

You are

I reply.

This is

we claim

It’s this.

Bug Bites: Zen and the Angry Child

You mustn’t suppose

I never mingle in the world

Of humankind —

It’s simply that I prefer

To enjoy myself alone.

– Ryokan

Into the morning blue he wakes as dark-eyed as when he greeted night. He hurls himself at me, his hair like snapdragon stalks unpruned along the fence of his fury.

“Idiot,” he grumbles. I am at a loss. First I tell him if he’s old enough to use that word, then he’s old enough to make his own breakfast. Then I change course. Thorns will not be the texture of our day. I slide from the bed and crawl across the carpet to my splayed and scowling son. Right up close, I say, “I love you, baby, and you love me. I always know it.” I wrap my arms around him and tickle his sides. As he wrenches himself away, he bites back the smile I catch peeking. “Even if you don’t feel it right this minute, I know you love me.”

“No I DON’T.” Cold simmer cuts up from under the blonde cloak shadowing his gaze.

When he was two, he declared himself a girl. Rainbows on his underwear. Sequins in his hair. His third and fourth birthdays were pink crowns and princess cake. In his fifth year, he shed the tutu and snapped on a fist. He has not unclenched it since, except in moments belly-flat on the floor or twined sticky into me. Moments when he forgets.

While the oatmeal simmers under its skin of sugared cinnamon, he arranges a dinosaur jungle on the floor. The T-Rex pounds at the lesser beasts. A barrage of high-impact explosions upends all the palm trees leaving half a dozen herbivores strewn across the killing field.

I watch him wander into the tangled garden of his imagination and take corners I can’t see. I tiptoe to the edge and consider joining him there. Does he need the company of others, of playmates, of me? My only child turns away and blazes a trail alone among his hedgerows. Is it labyrinth or maze? He is not reluctant to find his own way in. I wonder what, if anything, compels him to follow the thread back out again.

Returning home at the end of day, we trip our way to bed after fighting over dishes, teeth, bath. It is time to surrender to routine. Both of us need to waltz our way back to a rocking gait that smooths the friction at the edges where we meet. Three books. Three songs. Every night for six years.

He has a fairy blanket on the bed. It is the last vestige. He keeps it close even in the August swelter. With Tinkerbell bunched at our feet, we read Zen Shorts for the 400th time.

“Mommy, why is this book called that?”

“Well, the three stories Stillwater tells all come from Zen. And they’re all short.”

“What’s Zen?”

Oh geez.

“I guess it’s a way of living. It’s very old. Thousands of years, maybe? It has to do with making quiet places inside your mind and body.”

He twists away from me. Restless, ever moving. He is all proboscis and fire ant. A cement mixer. A quicksand man. I have had to learn to test my footing before every step. “You know how we talk about breathing when you’re wound up? Or when I heat up? Zen is about getting still. Like Stillwater in the book. Then you can accept things without needing them to be different.”

Zen Cliff’s Notes. Am I close? He’s humming and tapping his fingers in a pattern along the wall. I touch the edge of his leg just enough to make contact but not enough to capture his attention and raise his inevitable ire. “Even when there’s craziness all around you, even if a robber comes into your house or people say mean things, you stay peaceful inside yourself.”

“Yeah, yeah. Okay, okay.”

“It’s not just for kids,” I tell him. “Here.” I get up and go find the book of Zen poems a friend gave me back when time to play with meditation was there for the taking. Or rather, when we chose to see abundance in a clock face rather than just its pinching glare.

I open to Ryokan.

Here are the ruins of the cottage where I once hid myself.

“Okay, whatever. That’s enough,” he tells me. The gold ribbon marking the page hides down in the spine. He pulls it away and trails it down over the back. “Now you’ve lost your place,” he tells me.

“Good,” I say. “I was hoping for that. Now I can start at the next place.” I leave the ribbon free and close the cover. The cottage is far behind me. I am alone on my unmarked path but also tangled at the root with a boy whose opening is his own to burn or tend.

“Are you mad?” His grin crouches in the dry weeds. His eyes cut a path to me. He is ready to pounce.

“No, baby. I’m nowhere close to mad. I’m happy to be here with you, exactly like this.” I set the poems on the floor and open my voice for the first song.

Choose your Own

I pull him on top of me, say let go,

I want all of you.

Fully clothed but so very naked,

he asks

Is steadily increasing

closeness required? and I admit

(though not out loud)

that the way my ribs fall open

suggests, yes, I want him to enter

into me as tumblers

slip wide the hushed sliding

doors to a museum

where the glass wolf

eye and thinning lapwing feather

improvise a nest

in the last strip of silk from the wrist

of a deposed Saxon queen. This place

a low glimmer of a room

(it has only been rumored to exist)

and he is the unwitting key

as well as the single honored guest

passing us through virgin

corridors lined with relics

bearing no descriptions yet, one masterpiece

after another unfurling before our eyes,

no nameplate bolted into frame

and, come to that,

no frame.

He asks Can we have our vaults?

(his reliquary, a Parthenon of marvels

I circle in keen deference)

and I bite back the question

of whether he means spring

or safe (can we give and retain

with the same gesture?)

I say of course

and in this breath, speak a whole truth

with half a heart

threading its edge to one

who has the power of to draw

tunnels through concrete

and tilt the whole endeavor just enough

to spill us down to first strokes

of infant fingers through paint

whose color has neither been seen

nor imagined before

our eyes fall upon it. On me

he presses

open a fissure

between history and tomorrow

by defying logic

and lifting hands both

away from and into

gravity.

She Would Have Been

teary eyed still

smiling while

wringing her hands,

a half laugh

blushing

the quiver of her chin.

She would have been

shuffling in the house

slippers, her bird-boned

legs a dampered clapper

inside a bell of ruby velour

shushing the floor

and swaying her towards

Eddie Arnold

who croons from the bedside

table to fold

her in sleep.

She would have been

dusting powder

soft folds below her arms,

whispering powder

blue vein into crepe

chiffon before putting on

her lips. She would have been

calling me

Sugar.

Sugar, come over here.

Let me have a look at you.

Her hands

both

busy laying out the satin slip to wear

to her grave

and open

to me. Always opening,

she would have been

102, teary eyes still

like a mouth

turning up

for a kiss.

No Fixed Address

In the parking lot of the state college campus where Tee was staffing an exhibition table, Bug nursed. We sat in the back seat with the door open to a spring afternoon. Tee came around the corner to meet us, concern folding in a face usually at full sail. He moved to block us and pushed the door partway closed.

“What are you doing?” I asked. In my lap, Bug raised his eyebrows up and back to get in on the action. He didn’t lose his grip. Besides the perfunctory drape in an airplane or shopping mall, modesty had rarely factored into Bug’s mealtimes.

Tee shrugged and shuffled. “Everyone can see. We don’t know people here.”

This is not Then

It is impossible to run from the truth of him anymore. Without another man to hide behind, my naked heart receives the full blow. He walks into the house to drop off our son and he towers now in a way he never did. The sensation is not desire but it is similar enough to make the ground tremble. He is not the weak one anymore. That role is mine now.

Finally.

In the Saturday sun, Bug and I pound a volleyball back and forth before picking our way through brambles at the neighborhood park. Our path takes us around by the community gardens where folks till black soil into stirring plots. An erratic series of reports through the brush leads us to a basketball court glistening with a damp frenzy of male limbs. We watch for a moment before climbing a hill to a buttery yellow house trimmed in white.

“Right here, buddy,” I say. My feet find their way to the precise spot. For a blink, everything is a bright a June day. Bug climbs up behind me.

“Right here what?”

“This,” I say, spreading my hands, “is the spot where your daddy and I got married. He was there looking at me. This tree was absolutely covered in white blossoms.” Back then, two of the flowering trees had stood side-by-side. The arch studded with sunflowers had formed a bridge under the canopy of snowy petals. Now the larger twin is gone and just one tree stands bare. Eight years have passed. There isn’t even a trace, not one scar in the earth. Bug and I gaze all around the grass as it makes its tentative appearance into early spring. A few pink and purple pansies have been planted in mulch by the door.

“Everyone was in chairs here. Your grandmas and grandpas, all your aunts and uncles and cousins.” I retrace my steps backwards along the path I took holding my father’s arm. Oh, how I had laughed during that walk! The giddiness returns in a shiver. It is as potent as the moment I strode out between all the people I loved towards Tee, sweating and grinning there by the blooms.

“Were you embarrassed?” Bug asks as he follows me. We make our way through the trees and down to the tennis courts.

“Embarrassed? Why?”

“You were in front of all those people.”

“No,” I say. “I was happy.”

Bug darts ahead into an empty court. A brisk wind has been cutting into our collars. Bug follows the white lines, kneeling occasionally to press his cheek to the sun-warmed clay. On the neighboring courts, groups of doubles thwack and scrape, hollering at one another. We make our way around the back and look for the next trail into the woods. A man calls out and asks us to toss back a ball.

“Where?” I ask.

He shrugs and laughs. “Somewhere out there.”

We walk on, scanning. “I see it!” Bug hollers. Hiding in the grass is a lighter shade of green. He grabs the ball and races up to the fence. It is chain link nearly two stories high. Bug stops a few feet from the edge, pulls back, and hurls the ball. It sails up and over, clearing the top by at least twelve inches. Everyone on the court whoops and cheers. Bug’s pink face shines.

Early in our courtship, Tee spent weeks teaching me how to throw a baseball. First he had to un-teach me and then I practiced the awkward new pitch until it became second nature. In the field near his apartment, I could send that ball soaring over the power lines. He had to walk further and further back to catch it, and he smiled so big and called out his praise when it really flew. “Can you feel the difference? I can see it!”

The return of my maiden name has restored other lesser lords to their previous stations. Old muscle memory has regained its dominion. Solitude has settled back onto its cinderblock throne. This regime was not democratically elected, and so it happens that it is not easily unseated. I understand now that a coup d’epouse is an impermanent solution to the challenges of becoming a truly human creature.

That passage from the white-trimmed door to that lush duet of foliage is now only a neural pathway. It turns out I could not plant a new civilization in the soil of me just by crossing those 20 feet. Like the whole of the absent sister tree, the petals I remember are black earth now. Neither grass nor root has a record of our covenant.

Bug and I walk on. The yellow house where I donned my white dress recedes behind us. The park is not just the place where Tee and I married. It is the place where Bug celebrated his 5th birthday, burying pirate treasure in the volleyball sand with his preschool friends. It is the place where a visiting friend joined me on a stroll earlier this winter and we stumbled across fallow garden plots I did not know existed.

It is the place my son shows me that he has inherited not only his daddy’s pink glow but his throwing arm, too. Undoubtedly, he will be as ignorant of the rarity of his innate athleticism as he is of his fortune in the assignment of fathers.

Today, it is where I learn that I did love that man once. And it is where I practice walking under the weight of my own name in the other direction.

As it turns out, a swath of awakening earth is up ahead, warming itself for my arrival.

Born at Sea

Bug schlepped a canvas bag weighed down with five books and a beach towel to school on Friday. This was on top of his normal overstuffed backpack. With a parade of literary events, his class had been celebrating Dr. Seuss’ birthday all week. The grand finale had the kids lounging around the classroom on their towels like a pod of beached bibliophiles. It was a Key West siesta under fluorescent lights. When I picked him up, he told me someone special had come to his class to read.

“Was it Horton?” I asked. “The Cat in the Hat?”

He rolled his eyes. “They’re pretend!”

“Oh, so it was Santa Claus, then.”

“No! Guess for real!”

“Let me see. Was it. . . your daddy?”

His face lit up. “Yep!”

Tee is one of the three Class Moms for Bug’s kindergarten room. He is a regular volunteer and he manages all the electronic communication to keep the rest of us absent kin in the loop. The twinge of envy I feel about his extensive involvement is eclipsed by relief. At least my kid has a parent who is a solid presence in the school. (Even typing this, I am quelling the urge to explain all the reasons why this is the way it is, and how I am doing my best given commutes and job demands, etc. etc. Maternal guilt is a bottomless pit).

“So,” I said, turning into the driveway. “What did Daddy read?”

“Scuppers,” Bug said with a grin.

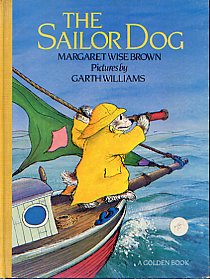

“Sailor Dog!” I cut the engine and twisted around to face him. “Boy, we read the heck out that book when you were little. ‘Born at sea in the teeth of a gale, the sailor was a dog.’ That is your daddy’s most favorite book ever.”

Bug jutted his chin. “How do you know?” This is Bug’s latest gambit: haughty skepticism. I take it as a sign of charisma and burgeoning self-reliance. This helps me bite my tongue.

My better self won out and offered up a shiny smile. “A long, lo-o-ong time ago, back when your daddy and I were first dating, he did nice things to try to get my attention.” I stretched toward him over the console and whispered, “I’ll never understand why, but he kinda liked me.”

Bug’s wall of snottiness crumbled. He unsnapped his seat belt and ooched forward. “Yeah?”

“Yeah. And you know how sometimes, when big kids or grownups like each other and start getting romantic and silly, they bring flowers and chocolate, all that lovey-dovey stuff?”

Bug nodded. His eyes were wide.

“So, your daddy and I had only been seeing each other for a few weeks. This was long before you were born. It was before we were married, before we really knew each other at all. One day, a package came for me at work. It was all wrapped up in paper. It didn’t say who it was from. I took it back to my desk and tore it open. Do you know what was inside?”

Bug shook his head. “What?”

“Scuppers.”

Bug took a second to absorb this. Then his face split open. “Scuppers?” He burst out laughing.

“Your daddy had sent me a picture book to show me he liked me.”

Bug rocked back with a whoop and collapsed into his booster seat. He laughed so hard he could barely catch his breath. “He sent you Scuppers? What?”

“Yep. I kept looking at it and turning it over. I couldn’t figure it out! He hadn’t even put a note in it. Some guys surprise you with a big bouquet of flowers. Not Tee. Nope. He sent me. . . ”

“Scuppers!” Bug snorted. “A kid’s book.”

I shrugged. “That’s when I knew your daddy was a giant goofball. And I also found out what his favorite book was.”

Bug shook his head and opened the car door. “I can’t believe Daddy. I just can’t believe he got you Scuppers.” He bounced out of the car and up the driveway. I grabbed the backpack and books he invariably forgets without a reminder from me. This time, I let him off the hook.

Bug knows his daddy loves him because Tee is there. Every time my kiddo turns, he finds his father all over again. Tee’s care is a physical presence. His love is relentless. (Long may it last)

Bug knows I love him because I lay with him every night and rub his back. Three books, three songs, without fail. We greet the dark together.

Bug knows that his daddy I once loved each other, too. I do not want him to forget. Our story is the prelude to our son’s. It was calm waters before it was storms and shipwrecks. It didn’t end the way storybooks are supposed to, but it was ours. It was love. All that remains of it is our son’s. There is treasure down there somewhere. It is his for the taking.

—

Brown, Margaret Wise. The Sailor Dog. Golden Books, 1953.