Packs of boys running wild. Moms grooving as they lower the limbo stick. Dads stalking their prey with the video camera. Pizza. Costumes. Gaggles of girls squealing between whispers. Two DJs in Hawaiian shirts, their strobe lights purpling the gym. Half a dozen conga lines crashing into each other. Justin Bieber. The walls thumping Gangam Style. Kids reaching their hands up, up, up, as they bounce ever closer to the sky.

Bug’s first school dance!

Category: Uncategorized

Happy 100 Days: 82

We are driving home in the almost dark and Bug drifts off to sleep. He stretches awake when I pull into the driveway, and I ask him again whether he wants pizza toast or eggs for dinner. He does not answer. When I gave him the same choices at Chicken School, he’d answered, “Lasagne and Thai food.”

“What’s it going to be, Buddy?” I ask as he slouches out of the car and yawns his way into the house.

“Mom, can’t we just sit on the couch and talk about it?”

This decision is clearly too much to tackle. I drop our bags in the doorway and follow him into the piano room. Granddaddy is in the den eating a sandwich and watching a show, no doubt gearing up for the vice presidential debates. I fold myself around Bug and he presses into me, resting his head against my chest. We do not talk for a while. I kiss his forehead over and over, just because it is so close. Finally, I ask again about dinner.

“Okay,” he sighs. “Eggs, I guess.”

Bug’s grandma is in Germany, so she is not here to help me figure this out. Also, I did not have the foresight to prep a meal. Such flashes of organization never strike twice in one week. I rise to go into the kitchen.

“Mommy, can you play something with me?”

“Can’t, Buddy. It’s time to make dinner.”

I start washing out the containers from Bug’s lunch. He follows me in, bringing the new science kit his aunt sent from Germany as a birthday gift. He opens it and digs through all the tubing and rubber gloves and strange pictures.

“What do I do with it, Mommy?”

I dry my hands and come over. The instruction booklet is long, and I tell him I cannot help him with it. “This weekend, baby. We’ll have lots of time.”

He sighs again and puts everything away. I have him set the table and wash his hands. He is still exhausted, still wandering around and looking for something to do. I remind him of his “H” collage for school. I set a magazine and some scissors on the table, but he can barely hold his head up.

Finally, dinner. We eat our spinach eggs, share the bacon, nibble at the cinnamon toast. We look together through the Kid’s Post and Highlights for words with “H” in them. Hockey, High Five, Third, Hidden. We find a picture of a hug. I help him cut and he glues the scraps into his journal.

Then it is time to clean up and get ready for bath. Bug finds a book sitting on the kitchen table. It is one of his new favorites, The Witch’s Supermarket.

“Mommy, can we read this book?”

I look at the pile of dishes, the unfinished laundry, the snacks still needing to be packed for tomorrow. I haven’t started the bath. If I don’t iron something tonight, I’ll be wearing yoga pants to work in the morning. Even with Giovanni watching the dog for the week, even with someone else paying the mortgage, all I can manage is another “no.”

And so I finally know this: loneliness is nowhere near the worst part of being alone.

“I really need to clean up. You could help me, and we would be done faster so I could read to you.”

I see my boy deflate. Even the book seems to droop in his hands.

“I really like this story,” he says. He is so tired.

“Sorry, baby, I can’t read it right now. I’ll read it to you at bedtime. If you are done helping, you can go look at it by yourself until I’m finished here.”

“Okay.” He trudges away.

Some days, I would give anything not to be a single mom. Okay, maybe not anything, but in certain low moments, the devil could show up with a contract and a fountain pen, and he’d walk away a soul richer.

I start the dishes. Then I stop.

How stuck in our ways are we? Really, how blind do patterns make us to their existence?

And how willing are we to come un-stuck?

We are not alone in this house. Yet somehow, we keep giving that truth so wide a berth, we can’t even discern its edges.

“Hey, kiddo. Let’s go ask your granddaddy. Remember that guy?”

We walk into the living room. Bug pauses, transfixed by Gary Oldman’s giant face on the screen. We chat for a moment with my father about Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, and then we ask if he would be willing to read Bug this book while I finish preparing for bath and bedtime.

“Why, sure!” He turns off the TV. “Get on up here, big boy!”

Piece of cake.

Bug ooches up onto the couch, pressing his insatiable body into his granddaddy’s frame. The old man takes the book. “Let’s see what we have here. Uh oh. Witches!”

And they begin.

As I putter and pack and start the washing machine, I overhear my father taking his sweet time. He puts on a cackling voice and even reads through all the disgusting signs at the Witch’s meat counter. “Eyes of newt, lizard’s gizzards. . . ” This catalog of dark magic gives me a few extra breaths which I offer up to Carolyn Hax and the other guilty pleasures of the Style section. This is my moment of nothing. A booming racket and a fit of giggles burst from the living room, and I hitch a ride on it, free and easy.

Easy?

Free?

Imagine that.

Happy 100 Days: 84

Some days, happy is not a feeling. It is taking a blowtorch to the invasive species. It is burning off the tangle that has choked off the native leaf. Remember those parasitic cuttings you pushed into your soil when you did not know better? Remember when the blossoms made you stupid and the fragrance made you swoon?

Remember the beautiful lie?

Those fine tendrils have twisted into steel coils. You see now, can’t you? How it happens?

Your folly then can be forgiven. Your devotion now cannot.

Some days, happy is not a bouquet. Some days, it is the making way.

It is the slash and burn.

And so, the purge.

(In the absence of a conflagration, an industrial shredder will do.)

Some days, happy is not a state of being. It is a trowel and a bucket of wet cement. It is an intention. A slog, even.

Some days, you are down below the frost line, down at the foundation only just dug, cramming blocks against the cold mud and plastering them into place. You are following the plumb line. You haven’t seen the sun in days.

You do not need to look up. It is still there. Trust me. It will be there again. But now, you are building a floor. You are making your shelter. You are climbing towards the sky.

Some days, happy is not.

And yet, you still find a box full of tools right there at your feet, and your hands are still at work, and the ground still holds.

Some days, the evidence suggests otherwise. But yes. The ground holds.

Happy 100 Days: 85

Ten Steps Closer to Home:

- Shake off the inertia.

- Call upon a generous and excited friend who happens to love real estate.

- Sketch out the picture of what you want, not just what you can manage.

- Choose to create an anchor for your family in a place you want to be.

- Look beyond the boundaries.

- Find a few places that give you the giggles.

- Skim mortgage lending sites.

- Click for quotes.

- Hatch a plan.

- Begin.

Happy 100 Days: 86

Rain and rain. A pyramid of monster cookies greets me when I return from the gray world beyond. Inside this cocoon, he has put beans to simmer in the crock pot and started baking the sourdough loaf. This one has a drizzle of honey to sweeten it.

Yesterday, as we meandered past storefronts and chatted with artists displaying their shards of glass and wooden eggs, he pointed out the Plow and Hearth. “What does that word mean? What is hearth?”

I tried to come up with the right definition, naming the specific thing (the inside part of a fireplace, no?) but also attempting to draw the edges of the concept with my meager words. I call up a picture of a Mary Azarian wood cut, that curl of smoke, the pot bubbling over the flame, an open chair near the table. A loaf, warm, waiting on the board. A jar of honey. A box of salt.

We walk on, and then it is the next thing. The child, the errands, the warming up for the next sprint.

Everything needs doing. Everything always does, no matter how much is already done. After stuffing the gift bags for Bug’s party with pencils and granola bars, I stop and curl up on the couch with the crossword from the Sunday Post. Giovanni is kind and lets me mute the football game to put on classical 90.1. A swell of strings pushes wide the walls.

The rain falls against the turning leaves, yellow poplars finally claiming their name. I mumble through the clues, calling out, “Four letters! Spy plane or rock band! Ends in X or O. We should know this!”

“I don’t know. ELO? NWA?” He slices asparagus and pepper, sautes garlic. In the oven, the loaf is rising, and he has started on the sauce for pasta. Much to my surprise, I complete the entire crossword. It may be the first time I have ever done so in one sitting. I do not know what time I arrived today. I do not know what time it is now. The couch no longer faces a clock. I forget to miss it.

It has gotten dark, and he has grated the parmesan. I hop up and put water glasses on the table, set silverware on the cloth napkins I gave him back in the winter. Candles, yes, and bits of romanesco, soft cones nestled among the shells. We eat and it is my turn to ask the questions about his tucked-away stories.

What is hearth?

Inside that word, sanctuary and warmth, yes? A place of returning.

I only a manage a rough sketch, but it suffices for now.

Happy 100 Days: 87

We swipe the last of the paratha across the bottom of the silver dish. This was something new, Chicken Kadai. (“How was it?” “Oh,it was kadai for!”) He pours the final splash of house white from the half carafe into my glass and then his. We are re-visiting a story that he knows but we rarely discuss. As happens when we are liking each other again, he finds a way to phrase the questions no one else would dare ask and I find ways to open doors with my answers. We are not the last to occupy a table in the restaurant. The other couple has only just started their entree, but still, the servers have long since ceased re-filling our water, so we tumble out into the brisk night.

“Your call,” he says. “Someplace for another drink?”

I consider this. It is enticing, 9:30 on a Saturday night. Cars whoosh along the boulevard. Colored lights and warm chatter invite from somewhere just around the bend. I decide to reel in the vision of what comes after this in-between. “No,” I say. “We’ll save a few bucks, like we promised. If we want a drink, we’ll buy a six-pack. Stay in. Finish this conversation under a blanket on the couch.”

“Wegmans?”

“Let’s go.”

In the store, we wheel the cart past the produce, past the bakery. He stops to squeeze a loaf of something dotted with pumpkin seeds. Then, he strokes another with a golden crust. “Like this,” he says, gazing at the gleam under the plastic sheath. “I want to get it like this. With that chewiness, you know?” We adopted a sourdough starter months ago. He is a much better father than I had expected.

I consider the cookies. He asks me if I want a treat, knowing I do.

“Let’s make some,” I say. “You have baking soda, right? Vanilla?” He nods. It has been too long since I have been in his kitchen. I used to know, but then there was the distance. He is out of butter now. He pauses at the beer and I leave him to it, heading on down to the dairy fridge. He is trying to watch his cholesterol, and the array of options is dizzying.

He approaches. “Country Crock?”

“I don’t think you can use it. See?” I point to the side of the margarine. “Not suitable for baking.”

“But that’s the generic. It says it is 48% oil. This one is 39%.”

I hold them up next to each other and try to puzzle through the fine print. “I don’t think a lower oil content is better for baking. I think it’s worse because it is more water. Maybe?”

Then he is holding up butter to compare. I find a butter blend, then two kinds of Smart Balance, one with canola oil and one with olive. We are trying to measure unknown quantities, the saturated fat in this one against the moisture content of that one. We juggle six different tubs. The poor butter sits alone to the side, denied entry but still on display just to advertise its failings. Its truth, its singular purity, is irrelevant in this contest.

“Fuck it,” he says. He dumps all but one of the tubs aside. The survivor lands with a thunk it in the basket.

We wheel out through the deserted produce section, grabbing a bunch of bananas on the way. He stops by the broccoli. “What is this?” He picks up a conical, fractal-studded oddity in sea-foam green. It is clearly brassica, but beyond that, it is a mystery. I believe I knew the name once but can’t call it up. “Romanesco,” he tells me. I realize I was imagining pieces never placed.

“What would someone do with it?”

“I don’t have any idea,” I say.

“Should we buy one and find out?” He digs around, finding the perfect one while I create a bouquet from a leggy artichoke, a rhubarb stalk, a yellow zucchini, and a single loose carrot. I tell him if we ever get married, this is what I want to carry down the aisle.

“You’re beautiful,” he says, laughing. He folds the romanesco into a plastic bag and places it in the cart.

Back at his place, I lose momentum for making cookies. I eat an unsatisfying square of Hershey’s chocolate instead. It is the only sweet in his kitchen, and it is waxy enough to keep me from coming back for seconds. He is made of stronger stuff than I am. Or maybe just different stuff. He opens a beer. We jabber on about important topics soon forgotten while he prepares the proof for tomorrow’s loaf. He realizes he is out of whole wheat flour. I remember that I am supposed to write something happy. I touch his back as he stirs white flour in. He never pours the discolored hootch off. He keeps it all in, everything unknown and alive, claiming “this is what gives it that flavor, you know?”

The sour whang lingers in the kitchen. In a nearby unit, neighbors bark at each other, their teary distress echoing at odd intervals against the balcony. That was us just last week. That was some other us a million years ago.

Happy 100 Days: 88

At the end of a long Friday at the end of a long week, I am missing my son’s birthday dinner because I have to work late. This is really okay, I keep telling myself, because I took him out to breakfast at Bob Evans and walked him to school myself. We carried the brownies for snack time in a hand-painted shoe-box. I will see him for a few hours on Saturday, and I have taken the day off on Monday because his school is out even though my university is not. And we were up late and up early, and then there is the actual swimming-pool birthday party next weekend, and and and.

But it is 3:50pm on the Friday of my son’s birthday, and I am upstairs in the windowless meeting room rolling around pre-fab tables to prepare for a series of presentations by doctoral students on public policy research.

This is my job. I love my job. I love my doctoral students, and I am curious about their passions, even when they start growing breathless over things like “financial liberalization in emerging market economies and international capital flows.” Yes, even that.

Several times in any given month, I seat myself in a room like this and drink from the information fire-hose. Sometimes it is a dissertation proposal. Sometimes it is an actual dissertation defense, the candidate as crisp and polished as a new apple but damp at the temples and speaking too fast. At weekly brown-bag lectures, faculty members talk about their projects. Peppered throughout the year are seminars by visiting professors, mini-conferences, and workshops like these where budding scholars present current research in a faux-conference setting in order to prepare for the real thing.

This program does a fine job expanding analytic capabilities and policy expertise, but most of the PhD students are just sort of expected to figure out how to present. Some are further along the curve than others. I have been wowed by a couple of rising stars who have employed both art and editing to design trim presentations with moments of humor woven into tightly organized structures. Most, however, cram 197 words on a slide, whisper and “um” through 25 uninterrupted minutes, and slog through table after table swimming with microscopic bits of data. Without a hair of irony, they refer to the endogeneity vs. the exogeneity of their various stochastic models, and their committee members let them get away with this gobbedly-gook. Everyone in the room, it is assumed, understands this language (where do you think the students learned it?) and anyway, the rest of the feeble-minded masses can just sit in the back and smile pretty.

At most of these things, I try to pay attention to the presentation itself. Masters degree notwithstanding, I usually only kind sorta comprehend the first and last quarters of each presentation. The middle chunk? The part that starts when the chi-squared flashes up on the screen? That’s where my bulb dims. So, I shift gears and attend to the presenter’s tone, body language, slides, tempo. The topic is beyond me, but I hope to give the student decent feedback on areas of strength and potential improvement. I am a quasi advisor, after all, so it’s nice to have something about which to advise when the best I can offer on the subject matter is, “Love how you had both an independent and a dependent variable! Super cool!”

So now it’s 4:00pm on the Friday of my son’s birthday and we are starting late because a few faculty members who had volunteered to provide feedback are not here yet. The students are here. More show up to support their peers (At 4:00pm! On a sunny, 81-degree Friday!), then more, until almost every chair in the room is taken, and professors keep sneaking in and grabbing the coveted back-row seats. We all finish our supermarket cookies and settle in.

The first presenter begins.

And she is good.

I mean it. Good! Her topic is fascinating. She is a stronger speaker than when she started the program a year ago. Her research explores the relationship between childhood obesity and participation in certain kinds of leisure physical activity. Specifically, she asks whether spatially expansive activities (she explains, God bless her, that this means things that need lots of room to do, like soccer on a field) are more significantly correlated to low body mass than, say, activities like playing Wii, jumping rope, or even recreational swimming.

Relevant! Easy to follow! Her data, though problematic in ways that the peanut gallery discusses with her, are clear. She actually takes time to explain them. She even had the foresight to keep the research questions simple enough to tackle in a 20-minute presentation.

It is 4:35pm on the Friday of my son’s birthday. After a short break, the next presenter begins. I take a breath and prepare to busy myself with my to-do list. My list does not stand a chance. Another fascinating topic. This one is about land use in Lahore, Pakistan. He has big maps illustrating population growth in the developing world, and I learn all sorts of things about suburban sprawl, corruption, and the history of colonization.

By the third, presentation, I have stopped watching the clock. This one tracks the policy implications of the de-institutionalization of people with intellectual disabilities in Virginia. This, in a state with active institutions 40 years after the Supreme Court case that was supposed to do away with such approaches to the special needs population? Curious! Appalling! So much more to explore!

It is 5:35pm on the Friday of my son’s birthday. I have a heap of questions to ask every presenter, and we have to cut off discussion because half a dozen hands hover in the air, people are sitting forward in their seats, and we were supposed to be done five minutes ago. I help one of the student organizers pack up the equipment. “This was really so good,” I tell her. “This was the first one of these I’ve been to. . .” I stop, realizing I’m not sure how to say it without insulting the entire student body.

“Where all three presentation were actually interesting? I know!” She says, laughing. We fold up the cords and tuck them away. “Usually once the equations come up, I’m a goner,” she tells me sotto voce. “I know I’m supposed to understand that stuff, but boy, it’s nice to hear a presentation that doesn’t take so much work to follow.”

We grin together. She actually had to get a half-decent score on the GREs to get into this program, and I know she has received high grades in her statistics courses so far. It’s comforting to know the bright people I revere occasionally feel like dimwits.

It is 5:45pm on the Friday of my son’s birthday, and I explode out onto the sunny plaza and stride to the metro. On the ride home, I give myself the delicious pleasure of reading a Jonathan Lethem short story in a rumpled New Yorker I found in my office. I have missed my son’s birthday dinner, but traffic smiles on me and I catch Bug at home a few minutes before his dad comes to pick him up. We open the last of the presents. We cuddle on the couch and read a sweet little Patricia Polacco book called Mrs. Katz and Tush. Larnell shares a Kugel with Mrs. Katz who is alone on Passover after her Myron dies. (“My Myron,” she sighs. “What a person.”)

It is six years to the day after my son pushed his way into the world. Life looks absolutely nothing like I imagined it would. That night, someone dropped onto my naked chest a real boy. I felt him land there, that complete and living human, and I whispered, “Welcome to the world, little guy.”

The world, you know. Such as it is.

It is 10:40pm on the Friday of my son’s birthday, and I am alone in the spare room of my parent’s house. The night may not be as sweet as I expected, but oh, how rich the flavor.

Birthday Boy

This is what I wrote on my long-ago blog just after we brought our little boy home six years ago. Happy birthday, Bug!

We made it through our first full night in bed. The near disabling fear of crushing or dropping you has finally begun to dissipate. The first few nights after you came home, my mind raced around like a skittish cat, imagining every terrible way I could lose you. I had to be a sentry, and ached to wrap you in a bubble of pure protection. I was so tense with watchfulness, your grandma had to buy me a sports mouth guard to keep me from grinding my teeth to powder during the night.

Now, I am starting to trust you are here for the long haul. When you wake to nurse, you rest up against my side, opening your eyes wide into the faint glow of the flashlight I keep in the bed and looking all around. I know you cannot see me yet, but I love to watch your deep violet eyes, try to catch their gaze as they trace the shapes of the bedroom. Our bedroom. Yours.

When you are finally satisfied and begin to drift off back into that mysterious place that holds you most of the day and night, I roll you back onto my tummy to sleep. Your face is towards me so I can watch you sleep. Your cheek can pick up the familiar rhythm of me. We both can sleep. All I need to be reassured, even deep in my own restfulness, is the occasional mew and wiggle against my belly. I know you are safe here. You belong here.

Sometime near dawn this morning, you gulped too much air and developed such a hearty case of the hiccups, the bed shook. I remembered you as an inside-baby, when your hics could send little earthquakes through my entire frame. I am still in awe of the you here with me, knowing you are the same you who floated and fluttered inside me all those months. When I run my finger down the string of beads making up your spine, I cannot believe I grew you. Flesh and bone, brain and body. You sprouted from that tiny germinated seed, and grew into you. Our Bug. Our son.

Happy 100 Days: 89

In the car, we talk about the special things a kid can do when he turns six. “You can join little league and play baseball,” I tell him. “Or be in the big kid gymnastics.”

“What else?” He asks.

“Well, once you turn six, you have to use your own metro card.”

He gasps. “I can have my very own metro card? Can we go get it right now?”

“We’re on our way to school,” I laugh. “And besides. You’re not six until tomorrow.”

“Oh, yeah.”

Wheat Bug doesn’t know is that I have already bought him a SmarTrip card and that I am heading to Staples on my lunch break to find a sleeve and a retractable clip just like the one he is always trying to steal out of my purse.

“What else can I do when I’m six?”

“Well, there are probably new rides you can go on at the amusement park. And I think you can use some of the big-kid high ropes elements at camp.”

“When I’m six, can I drink mouthwash?”

“Can you what?

“I mean,” he says in that exaggerated don’t-be-a-doofus tone kids master far too early, “can I use mouthwash.”

“Do you know how to use it?” This whole conversation has taken an unexpected turn. Since so many of ours do, I suppose I should stop being surprised by these detours. On a recent commute, I found us in a very detailed conversation about breast cancer. I had to puzzle out how to explain cell mutation in response to my kid’s increasingly complex questions.

We are nearing school now. From the back seat, he says, “Yeah. To use mouthwash, you kind of swish it around and gargle it and then you spit it out.”

“That’s a pretty cool thing to do when you’re six, huh?”

“Yep,” he says.

“Okay. If you want to, you can start using mouthwash.”

His grin lights up the rearview mirror. “Yay, yay, yay!”

We turn into the Chicken School parking lot, and we are jostling backpacks and kissing goodbye and rushing off to the next thing.

Later that night, after we have made the brownies for school, put on jammies, and opened a couple of birthday-eve gifts (including a Nerf football and Lego mining truck that arrived special-delivery at bedtime by Giovanni), we head in to brush teeth. Bug is bouncing out of his skin, hopped up on brownie batter and anticipation. When we are all done, I pick up the blue bottle of mouthwash next to the sink.

“You ready to try it?”

Bug darkens and backs away. “No.” His expression is grim.

“I thought this was a special deal for six-year-olds,” I say.

“Yeah, but Mom, my birthday is not until tomorrow.”

“Ah.” I set the bottle back down. Bug relaxes. “No reason to rush things, huh?”

“Yeah,” he says. He is already out the door.

No reason to rush.

Right. We’ll keep trying to remember that one.

Happy 100 Days: 90

While we are brushing teeth at bedtime, I somehow manage to elbow Bug in the face. I feel the crack, and immediately pull him into my soft belly. A split second passes and then he is wailing. Hot tears and even hotter anger seep through my shirt.

“I’m sorry, baby. Goodness gracious, that must hurt. I’m sorry.”

He howls into my side. “It’s your fault, Mommy!” Choking sobs. “It’s all your fault!”

I call down the stairs and ask my mother to bring us the ice pack from the freezer. She hands it up to us and I talk softly to Bug, finding a pillowcase to wrap around the pack. Bug is still clinging to me, yelling, “It’s your fault!”

“Yep, it is,” I say. I help him press the ice to his cheek then have him put on his jammies. I fill a mug with cool water for his bedside table. “It was an accident. I am sorry.” He keeps crying and scowling as the spot under his eye puffs to an angry pink. He reminds me about two dozen more times that I am to blame for his misery. I concede this fact.

Here is tonight’s small victory: My son does not hit me. He does not bite, kick, spit, or butt me in the face with the back of his head.

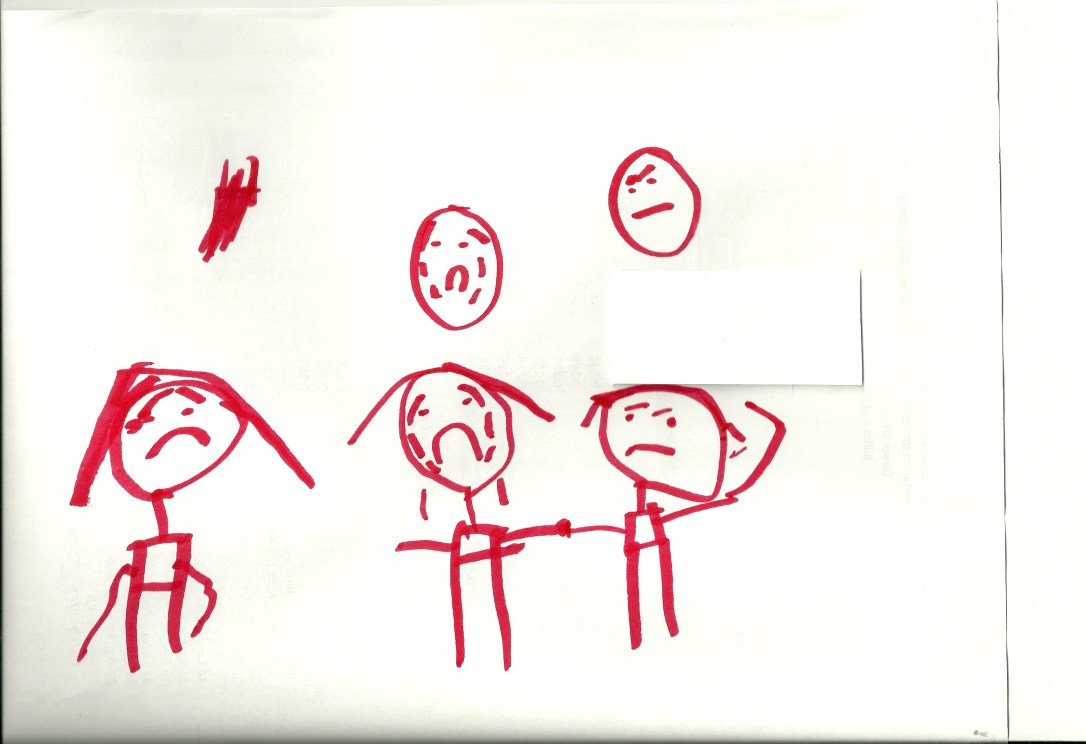

“Can I have paper for writing?” He asks. I dig up a clipboard from the clutter in his room. We crawl into bed and I begin to read as he writes on his paper with a thick red marker. Halfway through the first book, Bug interrupts me. “That’s you, Mommy.” I look over and see he has drawn on the far left of his page a frowning stick figure with a distressed look. I am impressed with the expressiveness of the eyebrows.

“That looks like a mean mommy,” I say.

“It is,” he says. He returns to drawing. I keep reading. After the next book, I look over again. He has filled in the page with two more stick figures. “Now you are sad,” he tells me, pointing to my double.

“Is that you with an angry face?” I ask.

“Yeah. I am punching you.”

“Oh. I see now.” He marks in little teardrops falling from the mommy’s eyes. “She seems pretty upset,” I say. “And he looks mad.” He draws the two faces again at the top of the page. One is crying and one is scowling. When he puts the cap back on the marker, I tap the page. “You know what you did, kiddo? You told your feelings to this picture.”

Bug reaches over and gives me the gentlest of swats on the shoulder. “Now I did the same thing to you for real,” he says.

I let it go. So does he. He pulls the page from the clipboard and drops it off the side of the bed. He starts practicing his letters. I start on the third book.

After we are finished reading, I tuck him against me into a full-body hug and sing “Baby Beluga.” My son’s new favorite approach to cuddling is to slip his arm under my neck and pull my head down on his chest. He wraps his hand around my shoulder and strokes my hair. It is an odd juxtaposition, my son holding me against him the way I have held him for so many years. I feel small and safe. I feel gigantic and cumbersome. I feel the echo of my voice off his fragile ribs and his unbroken heart.

Downstairs, I hear Giovanni come to drop off the dog. Her nails tippy-tap on the kitchen tile, a staccato counterpoint to the thundering footsteps of my parents as they wash up the dinner dishes and stash away the pizza stone. Bug’s schoolwork is on the kitchen table awaiting his teacher’s smiley-face sticker. A truck roars past on the muggy street outside. The air conditioner hums to life. The presidential debates begin.

I sing “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” and Bug sings along, his voice fading.

There’s a lake of stew and ginger ale too,

you can paddle all around it in a big canoe

He is under before I reach the end, but I finish anyway. I stay there for a few moments. His hand is against my ear, fingers tangled in my hair. He holds me as close as he can even in his sleep.

My son was angry at me. For the first time in 5 years and 363 days, he told me about it with words and art instead of with his hands.

So often, I sense the hugeness of the task ahead. Survive, save, support my child, teach him well, build a future. It is daunting. It can be very lonesome.

Tonight, I can feel my son’s strong pulse against my cheek. All around, the world goes on. It sometimes happens that in all that going on, people help. Sometimes, someone takes care of something that need taking care of. Someone walks the dog. Brings the ice pack. Pays the mortgage. Teaches the kids. Runs the country.

Sometimes, I can whisper my boy through his storm of feelings precisely because I am not alone.

What a revelation.

Sometimes, I am not alone.