“Mommy, do you know Mozart?”

I am pouring oats into the boiling water. “The cat or the musician?” Our long-ago pet’s musical mrawr? earned her the moniker of the great composer. The resident felines ran her off when we moved here in 2010. Bug only remembers the cat from stories and pictures.

“The musician,” he says.

“I’ve heard of the guy.” Stuffing the snack in his backpack, I tick off my mental list of tasks. The clock is inching towards 7:45. The pan on the stove is beginning to froth.

“Did you know,” Bug says, “that Mozart wrote all those songs when he was so young?”

“Yeah? Tell me.” Stirring in the brown sugar.

“And do you know Beethoven? What’s so funny?” He starts to chuckle. “He couldn’t even hear the songs while he was playing them!”

I am so in love with this county’s schools. “Did you know,” I say, “that I was listening to Mozart just last night while I was making the beef stew for dinner?”

“You were?”

“Yup. And there is a CD right over there in Grandma’s CD player that is all Mozart.”

Bug’s eyes widen. “Really?” He slips down from the table and turns on the player. He starts to scroll through the tracks. I finish pouring the hot oatmeal into a container for the car. He listens to bits, chords, the opening swell of Eine Kleine Nachtmusic then moves on. I gather drinks and school bags and keys.

Bug stops at a piano concerto and waits. Suddenly, he bounces up on his toes. “I know this song! I know it!” He lets his hands fall on top of the CD player and he peers into, listening hard. I seize this chance to spray the rat’s nest at the back of his head with detangler and work through the golden knot with a brush. He barely registers my presence. The notes rain down around us.

Halfway through the piece, Bug hits the back button so it begins again. He glances up at me as I shrug into my coat. “I know this one, Mommy,” he says again. His eyes are sober.

“Yes, baby. You do. That’s your song right there.” For a moment, we are both still.

Listen well, kiddo. Keep those ears open. Every song is yours. Every lyric, every splash of color, every rusted cannon, every story. The departed ones passed through this place in a breath and left nothing but their bits and strains. Except for a few, most of the names are gone, too. Now, it is yours. All this world, for you.

—

The other Mozart:

Tag: art

Happy 100 Days: 90

While we are brushing teeth at bedtime, I somehow manage to elbow Bug in the face. I feel the crack, and immediately pull him into my soft belly. A split second passes and then he is wailing. Hot tears and even hotter anger seep through my shirt.

“I’m sorry, baby. Goodness gracious, that must hurt. I’m sorry.”

He howls into my side. “It’s your fault, Mommy!” Choking sobs. “It’s all your fault!”

I call down the stairs and ask my mother to bring us the ice pack from the freezer. She hands it up to us and I talk softly to Bug, finding a pillowcase to wrap around the pack. Bug is still clinging to me, yelling, “It’s your fault!”

“Yep, it is,” I say. I help him press the ice to his cheek then have him put on his jammies. I fill a mug with cool water for his bedside table. “It was an accident. I am sorry.” He keeps crying and scowling as the spot under his eye puffs to an angry pink. He reminds me about two dozen more times that I am to blame for his misery. I concede this fact.

Here is tonight’s small victory: My son does not hit me. He does not bite, kick, spit, or butt me in the face with the back of his head.

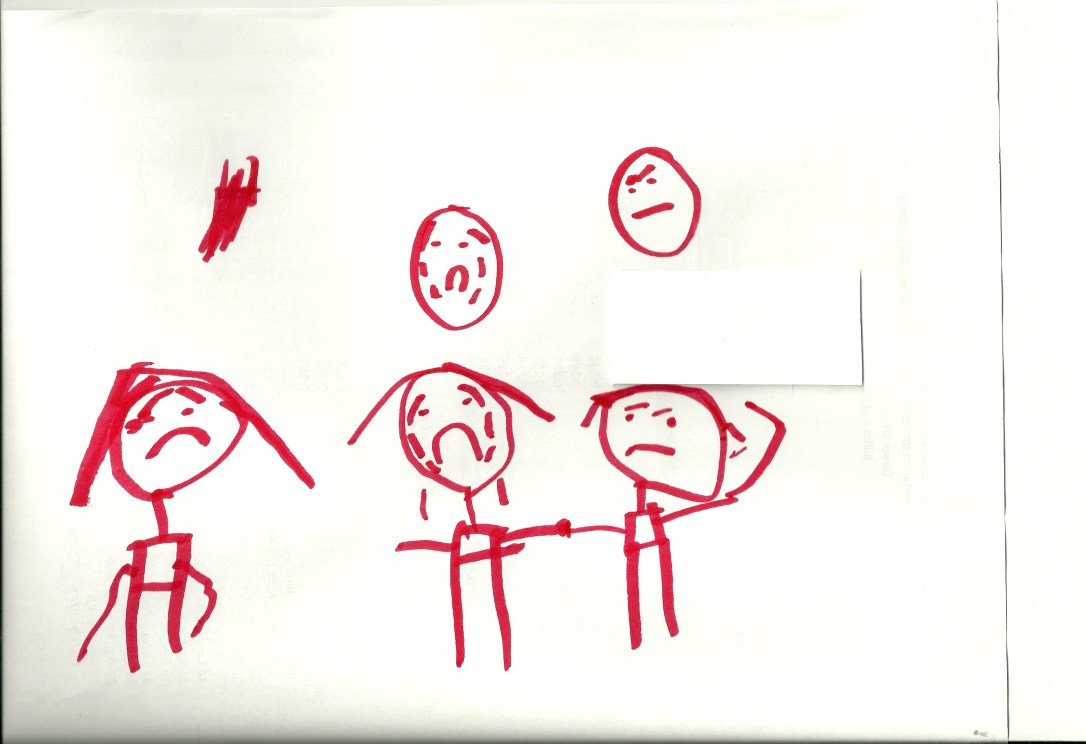

“Can I have paper for writing?” He asks. I dig up a clipboard from the clutter in his room. We crawl into bed and I begin to read as he writes on his paper with a thick red marker. Halfway through the first book, Bug interrupts me. “That’s you, Mommy.” I look over and see he has drawn on the far left of his page a frowning stick figure with a distressed look. I am impressed with the expressiveness of the eyebrows.

“That looks like a mean mommy,” I say.

“It is,” he says. He returns to drawing. I keep reading. After the next book, I look over again. He has filled in the page with two more stick figures. “Now you are sad,” he tells me, pointing to my double.

“Is that you with an angry face?” I ask.

“Yeah. I am punching you.”

“Oh. I see now.” He marks in little teardrops falling from the mommy’s eyes. “She seems pretty upset,” I say. “And he looks mad.” He draws the two faces again at the top of the page. One is crying and one is scowling. When he puts the cap back on the marker, I tap the page. “You know what you did, kiddo? You told your feelings to this picture.”

Bug reaches over and gives me the gentlest of swats on the shoulder. “Now I did the same thing to you for real,” he says.

I let it go. So does he. He pulls the page from the clipboard and drops it off the side of the bed. He starts practicing his letters. I start on the third book.

After we are finished reading, I tuck him against me into a full-body hug and sing “Baby Beluga.” My son’s new favorite approach to cuddling is to slip his arm under my neck and pull my head down on his chest. He wraps his hand around my shoulder and strokes my hair. It is an odd juxtaposition, my son holding me against him the way I have held him for so many years. I feel small and safe. I feel gigantic and cumbersome. I feel the echo of my voice off his fragile ribs and his unbroken heart.

Downstairs, I hear Giovanni come to drop off the dog. Her nails tippy-tap on the kitchen tile, a staccato counterpoint to the thundering footsteps of my parents as they wash up the dinner dishes and stash away the pizza stone. Bug’s schoolwork is on the kitchen table awaiting his teacher’s smiley-face sticker. A truck roars past on the muggy street outside. The air conditioner hums to life. The presidential debates begin.

I sing “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” and Bug sings along, his voice fading.

There’s a lake of stew and ginger ale too,

you can paddle all around it in a big canoe

He is under before I reach the end, but I finish anyway. I stay there for a few moments. His hand is against my ear, fingers tangled in my hair. He holds me as close as he can even in his sleep.

My son was angry at me. For the first time in 5 years and 363 days, he told me about it with words and art instead of with his hands.

So often, I sense the hugeness of the task ahead. Survive, save, support my child, teach him well, build a future. It is daunting. It can be very lonesome.

Tonight, I can feel my son’s strong pulse against my cheek. All around, the world goes on. It sometimes happens that in all that going on, people help. Sometimes, someone takes care of something that need taking care of. Someone walks the dog. Brings the ice pack. Pays the mortgage. Teaches the kids. Runs the country.

Sometimes, I can whisper my boy through his storm of feelings precisely because I am not alone.

What a revelation.

Sometimes, I am not alone.

Good People: An Elegy for Chris

He did not grow out of the cultivated earth of a literary tradition. He was Texas dirt, sunburnt and scarred. He banged into poetry sometime in his twenties and instead of slinking back and skittering away, he grafted it onto his body and sprouted there, all new.

He was not a particularly good writer when I met him. It did not matter. He drove his pen into the page, hammered those rough words out on a stage, and decided to be a poet. Bukowski and Ginsberg and Ferlighetti elbowed out the last of the complacency. He wrote of dark stink and revolution. He riffed off the speeches of great leaders with only a vague notion about how to organize a movement. Something more, something growling, pulsed through him, throbbing, feeding his voice.

He was so young.

We wrote together. In Dallas, on the cracked vinyl of diner booths, we wrote and wrote and wrote. One of us would suggest a prompt. We would write frantically for 10 minutes, read aloud without commenting, then write for 12, read aloud, write for 20. We could pass hours this way, whole lifetimes, galaxies dying off and starting again, no sense anymore of where one story birthed the next, one theme then the next, the rhythm of impulse moving in synchronicity over lukewarm Dr. Pepper and tattered pages.

For three months, maybe four, we were this toothed pair, fighting about everything and nothing. On Friday nights well past bedtime, we drove down I-75 to the slam in Deep Ellum at the Blind Lemon next to the auto glass dealer. We competed against our own team-mates and our own demon for the coveted perfect 30. He would get up there and hiss and hum his fury for that cash prize, barely enough to pay for two drinks. On Tuesdays, we went to Insomnia and took the mic just for the hell of it. On Sunday afternoons, we holed up in a windowless bar and team-wrote with a scruffy menagerie of rockers and poets and screenplay writers under a low shroud of smoke.

He was up for anything. He jumped at the chance to walk through the Dallas Museum of Art. He would pull over at a techno club well past midnight to dance among the goth teens. When his car was towed, we passed two hours in line at the flickering mausoleum of the impound lot, coming up with characters and laughing with our whole bellies. He discovered German barbecue places off the interstate, tried alligator tail at the cajun place, and introduced me to a proper Texas cheeseburger. We drove to Austin and crashed on a friend’s couch. He meandered wide-eyed through the State House, a place he had never visited in the lost years. He tracked down his state representative to ask her about road projects in poor communities.

I loved him a little and he loved me wild. His run-down pad off Walnut Hill had posters of Limp Bizkit on the wall and a full Nintendo game system he could barely afford. He had a twin bed. A sour couch. No savings. No degree. No plan. No pedigree.

But on that day my grandmother had the ladies over for bridge and he swung by to pick me up, he tapped some source of sugared light I had only just begun to sense. Never has a group of octogenarians so quickly puddled into fits of giggles.

He was complete already, and I didn’t know it. Neither did he.

He wanted to plan Big Things. Community-wide bilingual free poetry shows. Demonstrations in the park for funding for arts in the schools. He was firing on all cylinders with no direction of travel.

Except for one: Poetry.

He dreamed writing. He woke writing. When I urged him to slow down, to read, the practice the craft, I could see his jaw tense with the effort. He did not want to measure his pace. He did, though, because all suggestions were fair game. Then he would return to just writing writing writing. He got better and better.

He treated every other uncertain artist exactly as he treated his own self. “Get up there. You’ve got something to say.” He never let anyone sit in the back and play it safe. He did not wait for perfection or an invitation. He crashed the party. He grabbed everyone within reach and carried them with him.

“I believe the world is beautiful,” wrote Roque Dalton. “And that poetry, like bread, is for everyone.” Christopher Ya’ir Lane lived this.

Alas, no journey unfolds without flat tires and black smoke. Back then, a dozen years ago in the Dallas night, there were lies and drugs and there was another woman. I was leaving anyway to head back to Vermont to help a friend with a baby. So, the heat burned to embers and then ash. Sometime later, I heard that he had stumbled down the rabbit hole. The details were vague. He moved to Arizona. His siblings were involved. Who knows? I failed to reach out. Bruises, even if only to the ego, can make a heart cold.

I found him again virtually, years later after I was gone and back and gone again a few times around. He had his own beautiful family. A wife, a baby in his arms, then another. In the intervening decade, he had not stopped writing.

What did I say? He was not a good writer?

Now I have to admit that I didn’t understand the first thing about good writing. Chris had something to teach me I am only just now starting to wrap my mind around. Good is only this:

Doing it.

Just doing it, over and over, then doing it some more. He did not stop, from what I can tell, for longer than half a breath during that time. He had become a great poet. And what’s more, he had let that fire and fury carry him into projects that would make the Espada and Angeolou and even Roque Dalton proud. He put together youth slams. He became an organizer for the Alzheimer’s poetry project. He bridged the gap between rural and urban artists. He wrote and wrote, but he did not just do it from the back of the cave. He was a people’s poet. He shared, learned to make things happen, turned that charm into currency that could open the door to the ones for whom a closed door, or no door, is standard fare.

Christopher Ya’ir Lane was a far better writer and man than I gave him credit for. He never stopped. I wish I had known him later, that I had gotten over the small peevishness of our parting and welcomed him as a friend and as the gifted teacher he became. That is my great regret. But I am thankful that he inhabits a small moment in time and a living corner of my heart.

It is hard to know how to honor someone when the loss is so fresh. I can only say that this man’s life work is both humbling and inspiring. He did not wait around for the world to tell him he was good enough. He simply decided to love something, to make it multiply, and to cast the seeds of it far and wide.

So, for Chris, who shared that burning moment with me, I make this commitment:

I aim to crack open my rigid perceptions about what makes a piece, a project, or a person worth consideration. I aim to be impatient, to open my throat, to have the courage to believe in ink and voice to carry the art to life even if my doubt would surely sink it. I am to urge everyone I meet to follow their own bright pulse, blow past the doubts and the critics, and burn big, and burn loud.

Christopher Ya’ir was the best writing companion a girl could have during a fit of Dallas fever. I am grateful he unfurled his passion in my presence and showed me how it’s done. I ache for a world without him, and my heart goes out to his two beautiful little ones and to the wife who carried him over.

Goodbye, Chris. Your voice is with me, splitting open now in this turned soil, reaching for my own roots and feeding me the heat I did not even know I lacked. You live forever.

From the Mouths of Babes

At the end of preschool’s garden themed week, a picture of flowers with hand-print petals came home along with a plastic bottle terrarium containing threads of newborn sunflowers and beets sprouting from damp soil. This was also stuffed in the bottom of Bug’s backpack. An afterthought? Maybe an infant thought. Maybe a thin strand of desire nosing through the surface of things just long enough to catch the light.

With Drawn

Gather

Rose McLarneySome springs, apples bloom too soon.

The trees have grown here for a hundred years, and are still quick

to trust that the frost has finished. Some springs,

pink petals turn black. Those summers, the orchards are empty

and quiet. No reason for the bees to come.Other summers, red apples beat hearty in the trees, golden apples

glow in sheer skin. Their weight breaks branches,

the ground rolls with apples, and you fall in fruit.You could say, I have been foolish. You could say, I have been fooled.

You could say, Some years, there are apples.

For the second night in a row, my son is awake past 10:00pm. He is riding a tidal wave of inspiration. A paper sea churns around him. He draws with thick marker on a sheet of blank-backed leftovers from my father’s draft articles on adaptive management and my own half-hearted attempts at a screenplay. Without any concern for the neat lines of type on the opposite side, Bug splashes the blue ink across the surface of everything. He makes rocket ships and big-headed people, giant insects and treasure maps. When the clipboard is empty, he takes to the bedsheets. His lime green linens explode with giant butterflies and airborne letters. Even the bedside table has become canvas.

He is wearing me out. Eventually, I tip him from his perch. The wave crashes to the shore in a blast of salt and foam. Sobs wrack his body as I snap the cap firmly back on the marker and toss his creations overboard. “It is bedtime,” I say. My lips are tight. I am so very tired. The past week has been yet another chapter in the thousand year history of insomnia. Without good thinking to move us up and out, my own vessel runs aground in some desolate cove. While we languish, my visions of the promised land atrophy in tandem with my faculties. Neither tide nor wind is sufficient to carry us where we need to be. Without rest and a shot at a better life, I give my son only the leavings of my legacy of mistakes.

I long to give up, to curl into my own rumpled sheets. It is impossible while he is awake. He, too, spars with the night. What worries does he carry into his fractured dreams? With nothing to do but be, I crawl in next to my sobbing son.

“I’ll sing you one more song. What do you want to hear?” I have to ask this three times before he can calm down enough to decide. Finally, he chokes out a request.

“Big Rock Candy Mountain.”

“Okay, baby. Come here. ” Drawing him close, I sing it all the way through, slow and low. He surrenders his weight to my waiting shoulder one ounce at a time. When the song ends, he starts to stir. I ease into “Molly Malone,” welcoming him back to my arms. In Dublin’s fair city, where the girls are so pretty. . .

Well before the fever kills her, Bug’s breath steadies and his muscles soften. I carry on to the end so I can bid goodnight to Molly’s ghost, Alive, alive-oh.

When my feet swing off the bed, they splash into the eddying pages. I have to wade through them to get to the door. I can barely bring myself to look at my son again. His peace is too stark a reminder of what is required of me. How will this broken woman ever provide enough for this beautiful, bursting boy?

In a literature class in back in the wide-open days of college, a professor spoke with reverence of the tenacity of the great authors. She told us of the Brontë sisters, hunched over tables and making stories by candlelight. On bits and fragments in cramped script, they inked worlds to life. Sometimes, the scarcity of paper was severe enough that one of the girls would fill the page with tiny horizontal lines, then turn the page sideways and write across the previous words.

In my own bed, I train my mind away from our doom and breathe in the quiet safety of an in-between place. This inlet, our only home. We have paper in abundance to fashion both ship and sails. Oceans of ink. Currents of light. Our larder is full. We have song. We have each other.

We have enough.

You could say, I have been foolish.

You could say, Some years, there is this.