Going through photos of the last trip before my life changed, I see her. That me is there, radiating all the pain and exhilaration of the little mountain she climbed with her partner on their first day in Kaua’i.

I love that girl. She was hurting bad from a bum hip that would get replaced in a year, but she powered through it, sun-happy and heart-strong.

She started vanishing just a few short months later, replaced by a body-snatching invasion of Long COVID symptoms.

The worst of those symptoms? Post-Exertional Malaise.

Post-Exertional Malaise, or PEM, is the bane of my existence. It is the most disabling, most insurmountable part of my chronic illness journey. And PEM is something the vast majority of us didn’t know existed before it lay waste to us.

PEM is what it says it is. After exertion comes impairment. It’s not Post-Exertional Weariness or Post-Exertional Gotta Drink some Electrolytes and Take a Rest Day. The core of PEM is this: Exertion makes you sick. And the more you exert yourself, the sicker you get.

We’re talking about any and all forms of exertion.

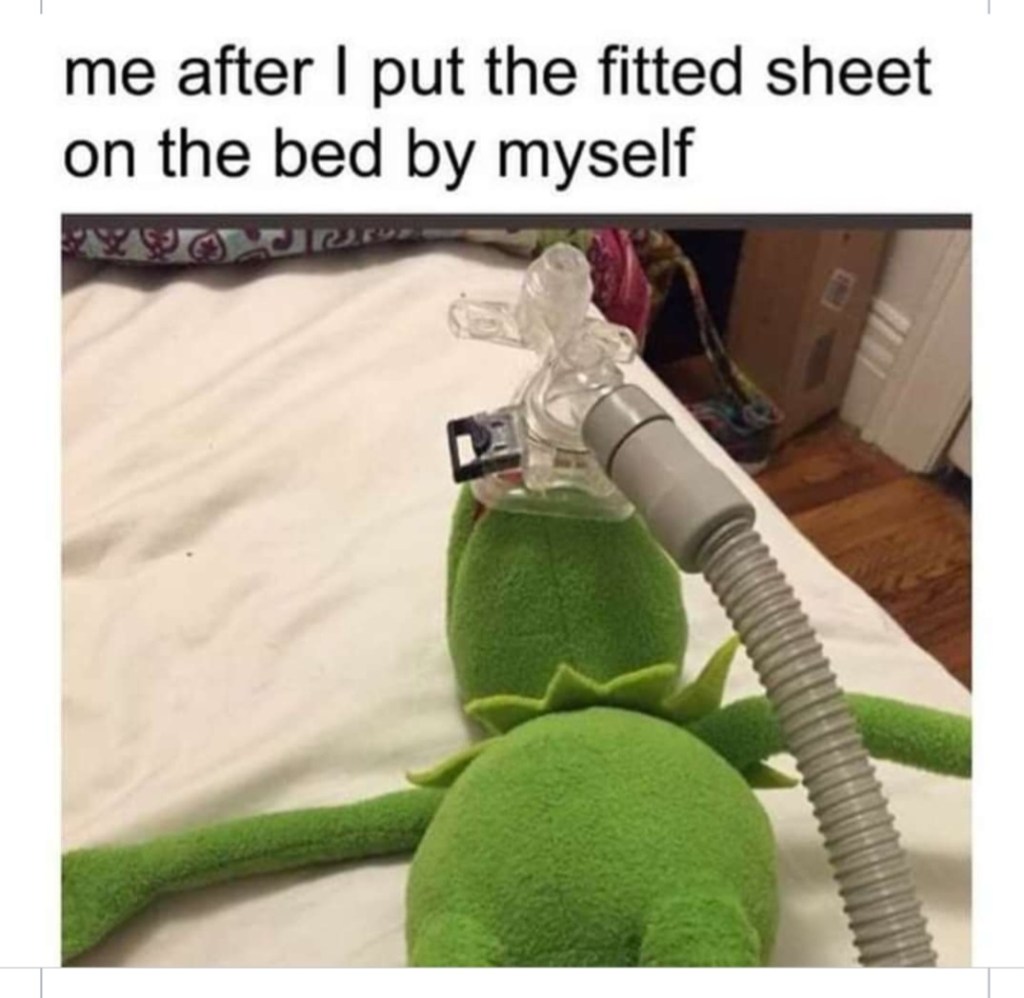

- The physical is obvious and it means marathons and loading trucks but also the most basic household chores. Even bathing. Even putting on your shoes.

- Add to this the cognitive exertion of things like knowledge work, project management, creative activities, problem solving, schoolwork, presentations and meetings.

- In there too is social-emotional exertion, which can include everything from managing your kids to just having a conversation.

- Sensory (or environmental) exertion, is about navigating and sorting all of the stimuli of day-to-day life, like screens, traffic noise, and weather.

- Some also include orthostatic exertion which is the effort it takes to be upright.

That last one may sound silly until you’re living with an illness like this and you suddenly find you can’t hold your head up during a Zoom meeting with your boss.

Most activities require effort in several if not all of all these dimensions at once. Through the countless small activities that make up a day – commuting to work, running to the store, filling out forms, scheduling a home repair – the exertion, though it seems minimal, adds up.

When a body is well, when it isn’t dealing with the runaway train of a post-viral syndrome, exertion may of course tire it out. Everyone has experienced the kind of weariness that comes with pushing too hard at the gym or at work. The average person might feel depleted for a day or so, rest a bit, then rebound. Indeed, pushing often makes these systems of a well body even stronger. More agile. It’s training 101. A hard workout or complex research conundrum may mean a day of two of soreness or mental weariness, but stamina and strength build over time.

With PEM, it’s upside-down world. Exertion doesn’t just contribute to normal tiredness. And it certainly doesn’t build muscle. It’s a kind of next-level fatigue that hatches from every small effort and multiplies, leading to system-wide impairment. The body reacts the way it does to an invader. Exertion kicks into gear an inflammatory or auto-immune feedback loop that triggers a cascade of symptoms. Fatigue, yes. But headaches. Vision problems. Nausea. Joint pain. Sore throat. More fatigue. Dizziness. Tachycardia. More fatigue on top of fatigue.

This reaction can last days. Weeks. For some people, a severe episode of PEM can go on for months, and even tip a person into full-blown, full-time ME/CFS (more on that in another post.)

This can happen after something as simple as going to the movies or chatting with a neighbor.

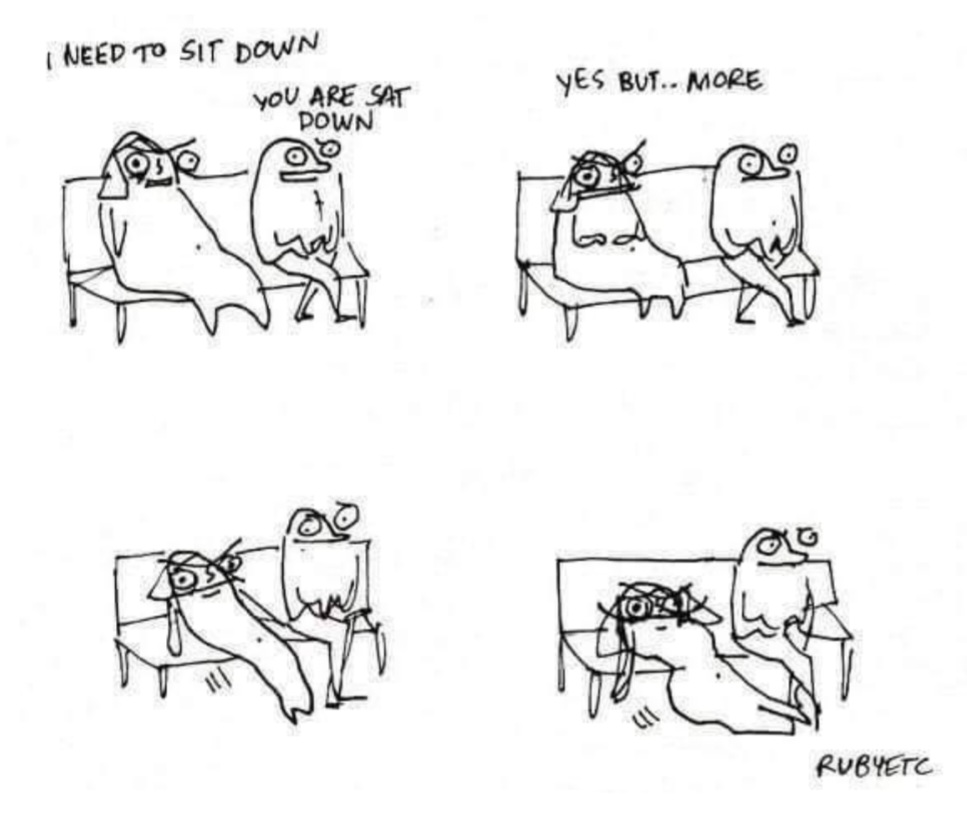

Here I sit in my living room, so worn out from vacuuming earlier that I had to nap. And now I’m up again, still shaking with exhaustion, wondering how to fill a quiet afternoon without exertion. I’m drained to zero but bored beyond belief and I can’t help but wonder: When activity becomes the enemy, what is left?

It’s crazymaking. For me, the most reliable medicine of my whole life has been movement. For every heartbreak or cataclysm, a movement elixir has helped me through it. I have found my way through periods of tough stuff (and boring stuff and super-great-but-just-so-much stuff…) by running, dancing, cycling, swimming, hiking, gardening, lifting weights, yoga, or just walking with friends. For every episode of depression, movement would trigger a system reset and return me to the world of the living. Even when I was injured or recovering from surgery, I could splay myself on the living room floor and dance with whatever parts didn’t hurt. Movement was the magic pill.

Now, movement is poison.

Not in some metaphorical sense. For real. If an activity elevates my heart rate or strains my muscles, it also floods my body with something so toxic I can’t think straight, speak, or stand up safely.

It sounds nuts. If you had told me two years ago that this was a thing, I’d inwardly roll my eyes and assume people were either lazy or not trying hard enough (I’m not proud of this) and really, if they just established the habit, they could regain their fitness. Reading this, you may well be thinking the same thing.

PEM is so poorly understood that even when I’ve been at the doctor’s office so dizzy I could barely finish a sentence, the nurse has said, “Start taking walks, it’ll make a world of difference!”

In our fitness-obsessed culture, it’s no surprise that everyone – from my physician to the person behind me in the checkout line – wants to prescribe exercise to fix what they don’t understand. But in this case, it’s dangerous advice.

As it happens, we’re not without wiser guidance. Medical treatment is a unicorn as there is no known cause and many doctors still dismiss PEM as depression or anxiety. What we have instead is pacing. Which is the simple word for establishing a baseline and not exceeding your energy reserves.

For me it might look like this: I figure out that I can walk, say, 10 gentle minutes and recover after a rest (no PEM! It’s a win!) So the next day I add 30 seconds to that walk. I try that for several days. If no crash, then I might bump it to 11 minutes. Give that a few days. And so on.

Through this methodical pacing, the moment I notice that an activity is elevating my heart rate or activating other telltale signs of exertion (like a sense of shakiness or a throbbing head), I pull waaaaay back. For the next few days, I rest aggressively with very little walking at all. It’s reset time. Back to baseline and start again.

Sounds tedious, right? Lord yes it is. The approach requires intentional focus and a commitment to honest analysis. Pacing is about as effective as any behavioral modification. Which is to say, it works only as well as the person doing it.

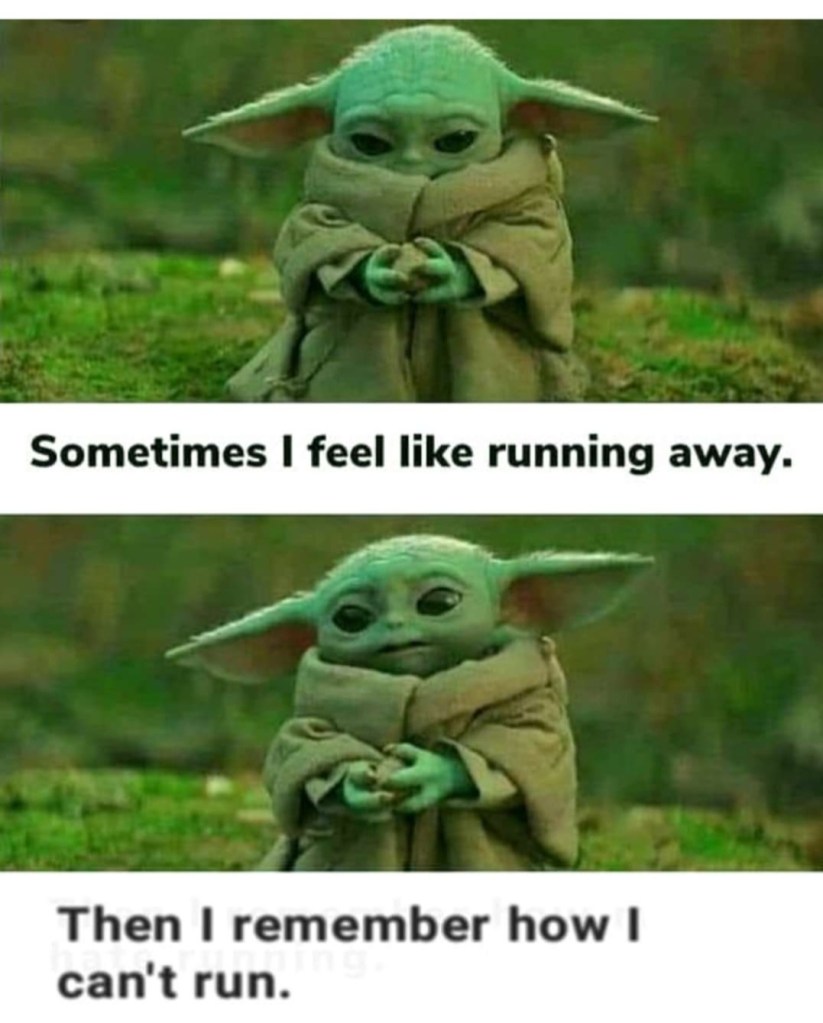

Seeing as how it runs counter to the deep part of me that longs to climb, sweat, dance my way to a healing endorphin flood, pacing hasn’t worked so well for me thus far. There’s too much rooted in me that wants to break free from this hell by exploding out from the treeline onto a mountaintop, glistening and panting and sore and alive.

Alas, slow and steady is the only way. To avoid getting even sicker, I’m starting to come around.

So for today, on this rainy Sunday, I will make a bowl of soup, walk the dog, then go back to bed for nap #2 (or is it 3)? Please join me in a little prayer that in the next couple of years, some tenacious researcher will crack the code and get each of us back to our mountain.

how vulnerable our we are

https://onbeing.org/programs/kate-bowler-on-being-in-a-body/

Thank you for this, you just introduced me to Kate Bowler and she is someone I clearly need to know!

my pleasure, bearing witness may be all we can do sometimes but it matters,

if only to those of us caught up in the struggle, it may get lonely but we are not alone.

The coronavirus is no ordinary virus. Yet we still fight over wearing masks and getting vaccinated. It’s difficult to imagine life without movement. May you find your way forward ❤

Thank you! It is fascinating when people say “back during the pandemic” as if it isn’t still now.

Life without movement is indeed life and it can even be a good life. That’s one thing I keep reminding myself!

Thank you for reading